Do Pastoral ICCAs exist in Contemporary East Africa? A case study among the Daasanach Community in Kenya

1, 3 Daniel Maghanjo Mwamidi *, 2Joan Gabriel Renom, 1, 4 Pablo Domínguez

ˡ Institut de Ciència i Tecnologia Ambientals (ICTA), Autonomous University of Barcelona, Spain.

² Anthropology Department / Institut de Ciència i Tecnologia Ambientals (ICTA), Autonomous University of Barcelona, Spain.

3 ERMIS Africa.

4 Laboratoire de Géographie de l’Environnement (GEODE), UMR 5602 CNRS – Université Toulouse 2, France.

* Corresponding Author: dmmwamidi@gmail.com

Abstract

Territories and areas conserved by Indigenous Peoples and local communities (hereafter: ‘ICCAs’) are commons systems containing significant biodiversity, ecosystem services and cultural values and has raised a strong interest among scientists. Despite the increasing acknowledgment of ICCAs by scientists at the global level, there is an existing knowledge gap of ICCAs in East-African yet literature review suggested the existence of such systems in this region. Thus, our main objective in this paper is to challenge the assumption that ICCAs are non-existent in East-Africa and contribute to put them in the center of the research arena of environmental conservation. We explored the existence of ICCAs focusing on Daasanach community from northern Kenya- through ethnographic inclines participant observation and semi-structured interviews (n=75) and data verification was conducted through 8 focus groups. We organised data in themes/domains as described by IUCN/CEESP Briefing Note no 10 examined whether the identified pastoral commons fit the criteria of ICCAs. Our findings evidence the important existence of Daasanach pastoral commons that corresponds to criteria of ICCAs. This challenges assumption in the scientific literature stating that traditional pastoral commons are rather irrelevant in today’s East African context. Such commons have played a central role not only for the local livelihoods, but also for the provision of ecosystem services which is aligned with the current definition of ICCAs. In concluding, we appeal for more research that would seek to stimulate a process of reclaiming a greater recognition to pastoral ICCAs in East Africa.

Key words: ICCAs, customary management, biodiversity, ecosystem services, Socio-cultural, ecological outputs.

Introduction

In the last two decades, a specific form of customary-based resource management de facto and/or de jure collectively governed by indigenous peoples and local communities has emerged, widely referred to as Indigenous Peoples and Community Conserved Territories and Areas (hereinafter; ICCAs (Borrin-Feyerabend & Hill, 2015). ICCAs are natural and/or modified ecosystems, voluntarily conserved by indigenous peoples, mostly through customary law (Dudley 2008). They represent a vast array of institutional mechanisms of governance (Borrini-Feyerabend & Hill 2015) for the collective and sustainable management of common-pool resources. ICCAs are nowadays recognized as a key management regime vis-à-vis local communities’ well-being, the conservation of the environment and global sustainability by major international policies and programs (e.g., United Nations Development Program, Convention on Biological Diversity and International Union for the Conservation of Nature ; Domínguez and Benessaiah, 2015; Kothari et al. 2012).

Awareness and recognition of the concept of ICCAs has been exponentially growing since its emergence as a result of decades of “fortress conservation” approaches drawing a strict line between human activities and nature conservation. It is often estimated that ICCAs currently cover up to 12% of the world’s land surface (Kothari et al. 2013). Indeed, ICCAs can probably be counted by millions worldwide, in terrestrial and marine environments, providing ecosystem services as well as livelihoods to millions of local farmers whilst contributing to the conservation of thousands of species and habitats (Borrini-Feyerabend & Hill, 2015). Yet, most ICCAs are not recognized for their conservation values (Kothari et al. 2013, 2015). This lack of recognition undermines their effectiveness to deliver sound conservation outcomes (Berkes 2009). There is a great deal of research showing that ICCAs are being threatened worldwide by many pressures, such as global market expansion or colonization, as well as the establishment of strict protected areas upon these territories under customary management that weaken their traditional institutions (Haller et al., 2013; Stevens 2013; Domínguez and Benessaiah, 2015).

ICCAs have been less recognized in East Africa given the strength of colonial approaches to conservation and the often negative interpretations of pastoralism the most practiced livelihood in the region. This attention gap to East African ICCAs is striking, considering the accelerated rise of scientific interest on the ICCAs worldwide or even in comparison of the knowledge about other type of ICCAs in the region, such as forest or water ones. However some early ethnographic works suggest the existence of pastoral ICCAs in some Kenyan and Tanzanian groups (e.g. Maasai case: Bernardi, 1955; Sukuma case: Tanner, 1955; Datoga case: Wilson, 1952).

Despite the examples synthesized above, the perception that there are no pastoral ICCAs in East Africa persists, is at least not with enough strength or “quality”, because they are too affected by historical transformations, to be worthy considered relevant for understanding of local society or ecological equilibrium. These assumptions may be mainly due to the characteristics of many pastoralist groups of this region, with absence of well-defined territories and with certain traditional management ways which made the common managed lands superficially seem to be open access lands. Also, due the significant historical disruptions which have suffered, with lands fragmentation and customary institutions undermined by the imposition of new structures of authority, among others.

It is in this context where the raison d’être of this work is based on, whose main objective is to confirm, through a case study, that beyond the clear indications previously exposed from the literature, in which you can only find references to the presence of pastoral ICCAs if you grasp tenaciously the anyway very scarce bibliography, the data obtained by field work supports the existence of pastoral ICCAs in East Africa. Therefore, our research had two specific objectives: (1) to explore the existence of pastoral ICCAs within the Daasanach Community (2) to describe the Daasanach management regime of pastoral commons as currently practiced; and

Thus, our starting hypothesis asserts that, considering the literature data and despite the various historical disruptions that they have had to cope, in East Africa there exists persist customary Community Conserved Pastoral Territories and Areas (pastoral ICCAs). The main questions on which we want to shed light and which guide the present text are: 1) Do ICCAs exist among the Daasanach, a community chosen by hazard among hundreds of others in East Africa, for the study of the presence of ICCAs? And, if they exist: 2) How are they managed, how important are they for local society and what is the state of its institutions in terms of legitimacy perception among the Daasanach? In fact, the answers to these questions could be a good first indicator of the relevance of pastoral ICCAs in other regions of East Africa.

With the aim to give answer to these questions, we briefly describe the case study and we provide an in-depth description of the applied methodology in this research. In order to provide a tidy ethnographic data, the results are organized under two subsections: 1) Community internal structure: the knowledge of the group’s internal organization is a fundamental aspect for understanding the complex scheme of cultural institutions on which the customary regime of resources management is based on; 2) Community’s livestock and grazing management: it is where we provide more specific descriptions on the Daasanach’s traditional pastoral resources management, their conserved areas and the customary institutions that takes part in this management. Lastly, we discuss about the data and we provide preliminary conclusions.

Context

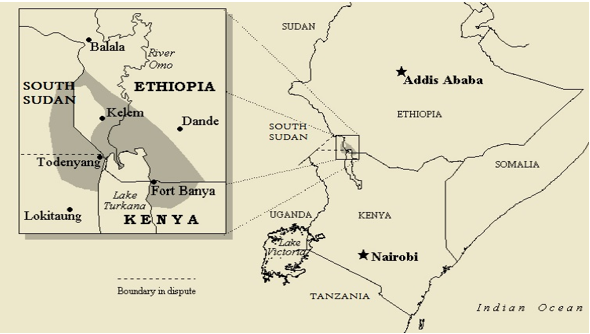

The Daasanach are Cushites of the Omo-Tana branch (Tosco 2011 in Cushitic Language Studies Volume 17). They occupying the northern shores of the lake Turkana, the lower stretch of the Omo river Valley and its delta, their traditional territory spread between a narrow strip of South Sudan, Southern Ethiopia and northern Kenya (figure 1). There are about 13,000 Daasanach living in Kenya and about 48,000 living north of the border with Ethiopia (IHSN, 2007; KNBS, 2013). The Daasanach territory is under a bimodal annual rain cycle, with a longest wet season from March to May and a shorter one from October to December. Nevertheless, the annual rain average of the region is very dry, usually under 200mm (Liebmann et al. 2014). Thus, it is an arid and semi-arid area with less than 5% of vegetal ground cover (Pkalya et al., 2004: 14).

Figure 1: Map indicating the Daasanach land (Source: Joshua Project.com)

They are primarily nomadic pastoralists, but they also perform fishing and flood-plain cultivation along the seasonally flooded river banks (Hathaway, 2009). Out of the Omo river delta area, their livelihoods depend foremost on pastoral resources (livestock) and somewhat subsistence fishing at lake Turkana. Historically they have maintained hostility with their neighbours Turkana, Gabra and at least Rendille and Borana (Fratkin and Roth, 2004). These conflicts have been increasing due to the historical disruptions which they have had to cope (i.e. territory fragmentation, colonial and post-colonial impositions, forced migrations, droughts increase, etc.) (Sagawa, 2010).

Present-day Daasanach community is grouped into eight tribal sections made of patriarchal clans (tur) related by marriage. The central defining principle of the Daasanach social organisation is age-set (generation-set) called (hari) which is defined by age (Almagor 1978 in Manchester University Press). Young men of the warrior (warani) class (from 14 to 35 years of age) provide labor for distant herding and also help in reinforcement of norms. Power on the age-set system is vested on an elite group of about thirty elders (ara). Elders are responsible to teach norms and taboos regulating the local management of natural resources and also assign directives to warani to reinforce natural resource utilisation values within Daasanach land.

Methodology

We conducted fieldwork between November and December, 2016 in 4 villages located in Ileret ward. We first obtained Free, Prior and Informed Consent from each village and individual participating in this study. We collected qualitative ethnographic information on the norms and practices related to the management of pastoral resources through field visits to different grasslands/pastoral commons, accompanying Daasanach herders during the dry season at the peripheries of National park. In each visit, we asked informants to explain the rules, norms and institutions in place to manage these resources. These in situ open-ended interviews helped us to inform the research design and contextualise the results from our semi-structured interviews.

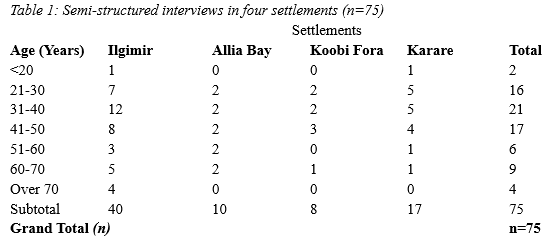

We administered these semi-structured interviews to 75 respondents targeting herders, elders seeking to: identify and examine community’s pastoral landscapes which are communally owned and governed by customary regulations; assess whether natural resources are communally utilised for the benefits of all with the community land; 4) asses whether customary management rules of the community land are viewed by locals as effective, and If violated, what are the consequences to the perpetrators and 5) examined qualitative outputs of ecosystem services of these identified commons. Data collected was verified through eight-sessions of 5-10 respondents’ focus group discussions of ages between 18-72 years (table 2)

Results

Data was analyzed qualitatively by organizing it in themes and domains as described by IUCN/CEESP Briefing Note No. 10 and Aichi Biodiversity Target 11. We used ICCAs’ elements as a yardstick in identifying potential ICCA/Commons in Daasanach land. In this section, we first present our finding which describes the Daasanach community’s internal structure and how governance/management of pastoral and natural resources is conducted. Secondly, we present the findings of the identified Daasanach pastoral commons that fit the description of ICCAs in terms of their qualitative ecosystem services outputs, communal utilization, customary-based management and governance of natural resources within these commons.

Daasanch Community Internal Governance Structure

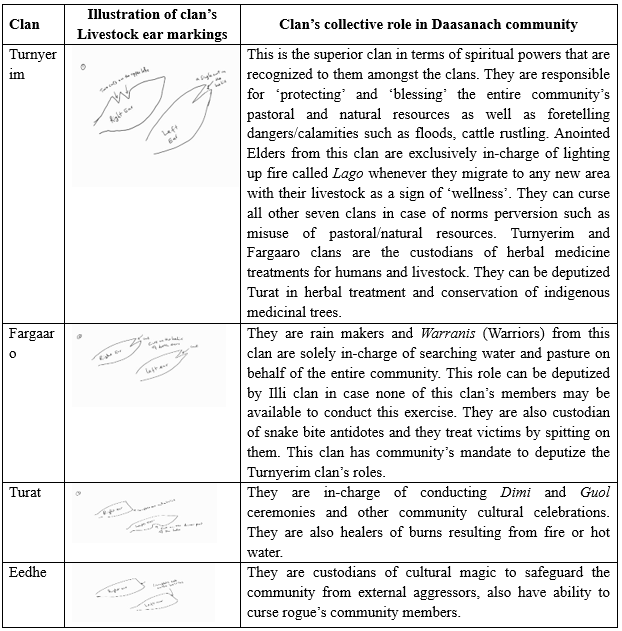

According to Elders, the Daasanach community has eight major clans of which, each one of the clan has a key role in ensuring stability and proper community functioning (table 3). These roles are distinctive of each clan, are based on the traditional knowledge and special spiritual skills rooted in their belief system and deeply attached to their indigenous landscape as well as pastoral and natural resource management. Also, these roles place them in a kind of supremacy ranking, though some clan may deputize some roles of other clan especially if none of the anointed member of the respective clan may be available (Table 3). All clan members graze their livestock together and, according to the report by the Ileret Ward’s Veterinary Officer, the number of livestock in the entire Daasanach community is around 31,000 cows, while goat and sheep counted collectively are 50,000, donkeys 3,000 and camel 400.

Table 3: Clans of the Daasanach and their collective functional roles in overall community synchronization

Pastoral Commons of Daasanach as potential ICCAs

According to our results obtained from interviews and FGD and observation, the Daasanach community have seven pastoral commons, four of which are: a) communally owned resources such as pasture, water, and biodiversity; b) utilized and managed by all members with equal rights collective governance and are the first beneficiaries of these ICCAs ecosystem services and c) protected and conserved through the their eight-clan governance system (table 3). The other three commons are overlapped by the Sibiloi national park, and thus according to Elders, they do not have direct management or utilization of resources inside the park and thus community’s customary management norms do not apply in day-to-day management of these areas.

According to elders, all Daasanch community members are pastoralist and they majorly depend on pastoral resources for their livelihoods. Pasture is very essential resource among the Daasanach land and the community has customary methodical mechanisms of managing this finite resources which involve distribution of livestock evenly across their indigenous community landscape which according to elders it: a) ensures full utilization and protection of scarce pasture and minimizes degradation of landscape. A forty four years old herder said “We are not allowed to graze in a single area for one month, because this may damage the ability of pasture to regenerate again. Some areas such as Kambi Turkana- Near Moite (at the southern border of Ileret Ward) have been left bear with no pasture and vegetation because other communities who graze in those areas do not care about tomorrow-they can graze in one place for over three or four months, but Daasanach are conscious about sustaining our livestock for many years to come”. b) Minimizes loss of the entire herd due to sporadic cattle rustling.

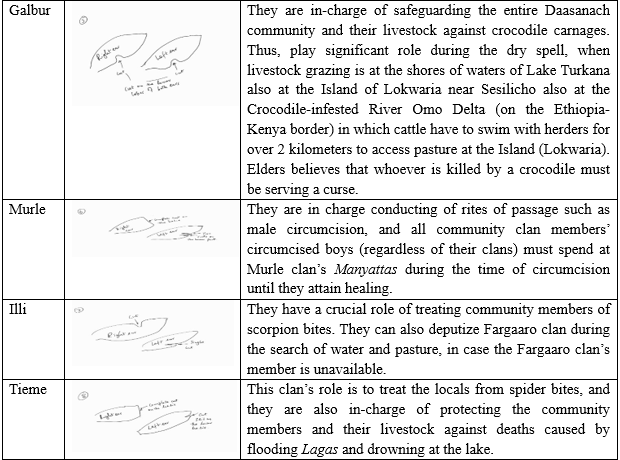

Another strategy employed by Daasanach in pasture management is through systematic migration to grazing areas, According to elders, herder migrate near the shores of the lake during the dry seasons in late September to February, while they migrate to highland on the Eastern sides of the Ileret during the wet seasons from March to July (figure 2). A forty-seven years old herder said “It is mandatory that the first week after the onset of wet season in March or April, all herders must move with their livestock up to the border of Daasanach and Gabra, Amarkoke and Turkana communities so as to utilize scarce resources such as pasture and water in this arid zone as well as ‘blocking’ our rival community from gaining access to the pasture inside our land. This has to be done from extremely north near the Kenya-Ethiopia border, to the Southern boundary bordering Turkana Community. It is mandatory for all herders to abide by this order which is given by our elders. Penalties and fines are attached to those who fail or delay to go with other herders during migration. Only older people are left behind with some few lactating goats and sheep for provision of milk for them”.

Figure 2: Longitudinal cross-section depicting the movement of herders from the lake to highlands during the dry to wet seasons respectively.

Qualitative ecosystem services from Daasanach pastoral Commons

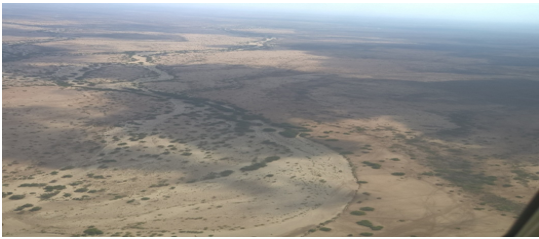

The seasonal laga Ileret’s watershed spans from Buluk and Surge hills, and also on the Southern Ethiopian side and drains to Lake Turkana. Elders reported that this seasonal river provides year-round underground water resources and is very essential during the dry seasons as it supports riverine ecosystem which is essential for survival of wildlife, livestock and the community (figure 3). A fifty eight years old elder said “Many of wild animals and bird species also depends on riverine forests as their habitat. Some animals come from Ethiopia to lick salt and eat some medicinal plants along the laga Ileret. .This laga has the highest numbers of guinea fowls and baboons that any other laga in Dasaanach land and also has diverse habitats for highly treasured leopards which we utilized its skin for celebration of the first born daughter in the family ceremony called Dimi. Other animal species found in these lagas are edible wild animals such as Oryx, Antelopes and Gazelles which we utilized as game meats only during the food scarcity and thus important for our livelihoods” But we only kill very few when there is inadequate food in Daasanach land- but that is a poor man’s diet… most of us who have plenty of livestock, we detest such a thing”.

Laga Ileret, yield culturally treasured red and ochre clay which is used for decoration among the Daasanach girls and warriors during the Dimi and Guol cultural ceremonies. A 34 years old herder said “We cherished ochre, and we conserve and protect it by all means, no one is allowed to mine it except during the seasons of dimi or gual”.

Figure 3: Aerial photograph of a laga in Daasanach land. These riverine ecosystems provides numerous shallow water wells for the community and livestock as well as other many ecosystem services (Photo: Daniel Mwamidi; captured at 7,000 feet above the ground).

At the deltas of lagas there are papyrus reeds which are used by the locals for thatching houses and as well as provision of pasture to livestock during the dry seasons. Elders reported that these areas are highly treasured because they harbor fish, crocodiles that they utilized as food and thus supplementing sources from livestock which are dwindling because of prolonged drought in this region.

Pastoral commons especially those around the lake are habitats to countless species of birds- some which are believed to have powers of having ‘skills’ of weather forecasting. A forty-two years old herder said “We highly depend on the calls from Bodidhe bird (Nightjar), Kireck (Yellow barbet), Nabus (Abyssinian roller), Dakal (Eagle) and when we see Kimidiriet (Marabou stork) sagging its wings like an umbrella’s shape, then it signifies the onset of a rainy season, and thus we normally start the preparation to be ready for migration. These birds’ behaviors are very accurate and all Daasanach rely on them for weather forecasting”.

According to elders and herders, all community riverine ecosystems are conserved, governed and managed by the community eldership who transfer some authority and mandate to warranis (ages 18-35 years) for reinforcement of the norms. A thirty years old Herder said “We are not allowed to graze large animals such as cattle, donkey or camel within riverine because they may degrade these areas quite fast, and thus we only graze young/small sized livestock such as calves, goats and sheep may graze in these areas as they may not pose dangers of degrading the area. Moreover, the amount of pasture they consume is less as compared to full-grown cattle, donkey or camel. We are also not allowed to cut any tree because many of such indigenous trees are our ‘pharmacy’- we utilize them as plants as medicine because there are no hospitals within, and the nearest one is hundreds of kilometers away. We also treat our livestock using these trees and thus we are obliged to conserve and protect these trees because without them we will all die with our livestock!” Elders reported that tough penalties are attached to anyone who is caught destroying riverine forests. A fine of a full grown bull is a tag to those who contravenes these norms.

Elders reported that indigenous trees are considered as treasure among the Daasanach and thus they protect them by all possible means. A fifty nine years old elder said “We do not allow anyone to destroy trees in our land, in fact, we do not destroy manyattas when migrating to new areas, This protects trees as no new manyattas are built in subsequent migration. We always rotate in a same pattern and camp on same areas around Daasanach land, and nobody owns manyattas- they all belongs to one family-Daasanach community”.

Indigenous medicinal tree species within pastoral commons

Daasanach Pastoral commons have numerous indigenous tree species that are utilized as herbal medicines by and elders reported that Daasanach community depends majorly on indigenous medical tree species because of unavailability of conventional treatments within Ileret Ward. Elders mentioned various indigenous trees species that are exploited as herbal medicines which are conserved and protected through strict customary restrictions. A sixty-eight years old village elder said “Curse will be upon anyone who destroys trees that is used to cure diseases among our people. Cutting a tree is like killing a person directly because the medicine saves life of sick person”.

Some indigenous medicinal trees species which Elders and herders mentioned include:

i. Dermech (Grewia tenax) tree species is used as a detox to cleanse the body from impurities. It is also eaten by goats/sheep and camel as pasture.

ii. Lomadang tree species is used to treat major reproductive afflictions such as infertility, vaginal discharge, menstruation disorders and relieves lumbar pains in women, and also used to treat infertility in livestock.

iii. Gieliech tree species- Used for promoting fertility among women and men.

iv. Nanguda (Rubus steudnes) tree species- Used for treating fevers in humans and livestock.

v. Nyabangitang (Rhus vulgaris) tree species- Use for deworming internal parasites of the liver and intestines, ringworms for both humans and livestock.

vi. Gorguriech (Euphorbia heterochrona) tree species is used as a broad-spectrum herbal medicine (for all infections) for both humans and livestock.

vii. Miede tree species- Locals consider this tree as the most ‘sacred’ tree in Daasanach land. According to Elders and herders, Miede tree is used to make Lago- which is the first fire made immediately upon herders’ migrating in a new area which has to be conducted by an anointed member of the Turnyerim clan.

Elders reported that Daasanach depends entirely for natural environment to provide important food elements such as vitamins, medicines, proteins, minerals among other important elements required by human body. For instance, locals depends on riverine ecosystems for wild vegetables such as amaranthus, and edible wild mushrooms for food, and are in plenty during the rainy seasons and reduced in dry seasons. Some of the wild vegetables that elders mentioned are: Nyelim/gilieny (Cordia africana), Mier, Kada (Harpephyllum cuffrum), Gaba (Ziziphus mucronata), Damich, Barbar (Senna didymobotrya).

Water resources within pastoral Commons

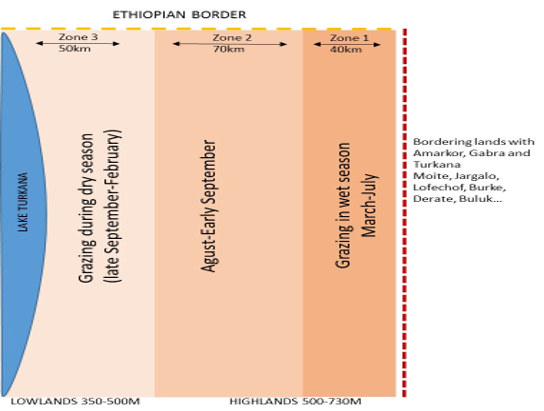

According to elders, Daasanach have a well-organized system of protecting water wells found along the river-beds of lagas (figure 4). These shallow wells are protected and elders reported that whenever herders migrate to new areas, they are require by customary norms to refill them with sand so as to avoid excessive evaporation and thus minimize this scarce resource in this arid region.

Figure 4: The riverbed of a seasonal river in Ileret which provides myriad of shallow water wells for community and livestock as well as pasture for goats, sheep (Photo Daniel Mwamidi).

Water is managed by the Daasanach Warriors (warani) through three methods:

a) They fence around the shallow well using thorn twigs of Acacia drepanolobium and Acacia reficiens so that livestock would access water in smaller portion bit by bit rather than letting them inside defecating and urinating on the entire water well and reducing its quality. By so doing, herders will ensure that water would not be degraded faster than pasture. A sixty years old elder said “pasture without water is useless, and it is better to have more water and less pasture than having more pasture without water” and thus water is regarded as paramount pastoral resource de facto, in these areas. He continued saying “Whenever we migrate to a new place and there is plenty of pasture, there may be dangers that the grass may remain, while water is depleted or spoilt faster, and thus being forced to migrate to other areas and leaving a lot of pasture behind- which is a very hurting thing to us!, so we always ensure that there is balance between water and pasture. It is better to finish pasture and retain water, because water is life”;

b) Whenever there are deeper water wells that are difficult for the livestock to drink from, the warriors/herders would fence around and put narrow entry-ways that is guarded by thorns and thus they would organize themselves in relaying pattern or one would fetch and pour water in a water trough for livestock to drink. One will fetch the water from the well/borehole and relay it to the next person who would relays it to subsequent person up to the point where animals are to drink at kadich (water trough) with over 20 cows drinking simultaneously. This is done so as to prevent livestock from getting access to water directly and thus filling it up with sand. Contraveners of these practices are beaten severely by warani and fined a full-grown bull and forced to slaughter it for herders and elders to feast.

c) Elders and herders reported that it is a requirement to refill the water wells with sand while migrating to a new are and thus former water wells are protected from excessive evaporation and loss of water. A seventy year old elder said “We normally protect water wells because if you leave them open there many dangers that may occur, such as excess evaporation because herders may stay for over five months before going back to the same area. Also, if our enemies come and find an open well, they may camp there or even do bad things like poisoning water for us and livestock! Also, it may be dangerous for wildlife to fall inside the uncovered wells”

Discussion

Since a general understanding of a local institution as “(…) a set of rules put into practice in particular contexts; constructed rules, agreed upon and modified by the users of the resources in specific communities.” (translation from spanish: Merino, 2004: 128) , and under the light of the above data, it can be stated that the Dasaanach of Ileret Ward have a decades old if not centuries old management system for their pastoral resources and grazing regimes governed by customary institutions embedded in the structures of the social organization, within segments of belongings to different levels (kinship, clan, age group, etc.), also deeply linked to the beliefs system and to the local ecologycal knowledge, adjusted to deal with the local environmental conditions of aridity with random variations in the droughts and rains regimes, shaping a real biocultural system. Within this system, the main decisions fall on the elderly hierachy and passed to higher ranking age sets to the lower age sets of warranis.

It should also be noted that, based on their territory management, it is evident that their knowledge and practices do not only respond to logics focused on livestock needs, as suggested by Bollig and Schulte (1999) for the Pokot case, it also implies the knowledge of the cycles and ecological needs of the graze lands, of the vegetation in general, of the fauna and even of the water, in order not to exhaust them. This logic of resource protection and conservation in the management strategies of the Dasaanach is made clear, for example, in the establishment of special protection and conservation areas or in their customary norms of movement, trying to minimize their impact on the environment by a maximum dispersion on the territory so as not to overgraze an area. In this sense, for example, McPeak (2005) points out that degradation of certain grazing areas among the Gabra is usually associated mainly with a maldistribution of herds on the territory (2005: 194).

Thus, as is shown by the data obtained, for the Dasaanach the dispersion on all the territory is obligated, under risk of sanction. At the beginning of the wet season they must begin grazing from the borders of their territory, not being able to remain more than one month in the same grazing area, especially in those under special protection regimes. They also have rules that prevent the overspend and depletion of resources, such as not being allowed to destroy the temporary settlement huts (Manyattas), to avoid the increasing of deforestation as well as refilling water wells with sand while migrating so as to minimize excessive evaporation and protecting wildlife from falling into them.

Something that has been much discussed in the literature on pastoralist groups and which would seem to contravene this statement is the traditionally large Dasaanach herds, despite occupying an arid territory. However, several authors have shown that such cattle accumulation is not only a strategy related to the prestige or to an individual advantage interest on the common resources. The non-limiting size of the herd can also make a lot of sense as an adjusted strategy to the particular conditions of an environment such as the East African one (Homewood and Rodgers, 1987; Leeuw and Tothill, 1990; McCabe and Ellis 1987).

Such is the Dasaanach case, whose groups live in contexts characterized by frequent robberies of cattle, strong hostility between groups, limited access to water points, limited availability of labor in each family group and the existence of strong periodic cycles of droughts and epidemic livestock diseases. Thus, as McCabe (1990) shows for the Ngisonyoka Turkana pastoralists, a group that lives in such an ecological environment, the environmental characteristics and the relationship with neighboring groups also play a strong role in regulating and limiting the herds size, as well as in their mobility and access to the different grazing areas.

Therefore, it becomes evident that the pastoral resources of the Dasaanach of Ileret Ward are not open access and comply with the principles that Kothari et al. (2012) indicate as characteristics of the ICCAs. They have communities that manage the natural resources of their territory by a communitarian way, through customary institutions of governance and sanction to the contravenors, which are the result of collective arrangements and decisions and are aimed at protecting and conserving the environment and the natural resources from which are benefiting the whole community.

Also, as mentioned, within these territories there are many areas with special protection (Lagas) — very importantly riverbank forests — which are partially excluded from grazing — with the exception of calves and small cattle — and where the resources use is strictly regulated. These are areas that, without intent of establishing a comparison, allude to other customary pastoralist institutions, such as the Ngitili Sukuma, the Alalili Maasai or the Milaga Gogo, and in turn evoke other community management systems such as the Agdal of the high Moroccan atlas described by Domínguez (2010).

The fact that, because of the expulsion and exclusion of the Dasaanach from their traditional territories, currently encompassed within the Sibiloi National Park, these communities have ceased to see this territory and its resources as something of its own to protect under their customary norms, shows that, beyond the cultural values that the territories and areas of community pastoral management means, and beyond their historical, social and economic value, these traditional forms of community management of the territory can also be of great environmental value. Not only because of their importance as configurators of the landscape (Little, 1996), but above all as possible practical and effective ways of protection and conservation of natural resources. Well adjusted ways, deeply rooted in the local logics, values, beliefs and representations of the communities granting them a local legitimazy and strenght that rarely attained and as effective as any other top-bottom impossed approach of protecting and conserving the ecosystems.

Conclusion

This research among the Daasanach of Illeret Ward is a first approach to our fieldwork on the customary communal management of the pastoral resources in East Africa, which has proofed to be an evocation to the wealth and difficulties of the East Africa pastoral ICCAs. We are aware of the needed to go deeper in this matter, with a wider time field work that could allow to contribute with a more in-depth ethnographic analysis. Nevertheless, already from the obtained data, we can state that the Daasanach are an East Africa pastorilst group that has pastoral ICCAs deeply embedded in its social and cultural structures and make a fundamental key of their governance of local ecosystems and natural resources, greatly enrooted on their traditional ecological knowledge.

Also, although they are institutions that are in a delicate situation, facing importante challenges and transformations, specially from state agents, such as the biodiversity loss in all their territory or the land loss due to the Sibiloi National Park interventions, apart from the economical impact that his must have had for the Daasanach, in the opinions of the local people regarding such loss of territorial control, it becomes evident that these institutions still have a great legitimacy and key importance, as they are perceibed by the Daasanach as useful for their welfare and necessary for avoiding resources depletion. We suspect that this is the situation for thousands of similar systems throughout all East Africa and hence, this work should be only a spearhead seeking to awaken a process reclaiming a greater recognition to pastoral ICCAs in the region, which we presume (research in the next years will confirm it or reject it) are a key managerial regime in favor of social peace and environmental conservation for East Africa.

References

Acheson, J.M. (1991 [1989]). La administración de los recursos de propiedad colectiva, en Plattner, S. (ed.), Antropología económica. México, D.F.: Alianza editorial, pp. 476-512.

Bernardi, B. (1955) The Age-System of the Masai. Citta del Vaticano: Pontificio Museo Missionario Etnologico. Disponible en Human Relations Area Files (eHRAF)

Birley, M. (1982). Resource Management in Sukumaland, Tanzania. Africa, Vol. 52, No. pp. 1–30.

Bollig, M., Greiner, C. and Österle, M. (2014). Inscribing identity and agency on the landscape: of pathways, places, and the transition of the public sphere in East Pokot, Kenya. African Studies Review, Vol. 57, No. 3, pp. 55-78. doi: 10.1353/arw.2014.0085.

Bollig, M. and Schulte, A. (1999). Environmental change and pastoral perceptions: Degradation and indigenous knowledge in two African pastoral communities. Human Ecology, Vol. 27, No. 3, pp. 493 – 514.

Borrini_Feyerabend, G., Kothari, A and Oviedo, G. (2004). Indigenous and Local Communities and Protected Areas Towards Equity and Enhanced Conservation [online]. Best Practice Protected Area Guidelines Series, No. 11. IUCN – The World Conservation Union. Available at: http://www.iccaconsortium.org/wp-content/uploads/Guidelines-11.pdf

Cabeza-Jaimejuan, M., Fernandez-Llamazares, A., Fraixedas, N., López-Baucells, A. and Burgas, D. (2016). Winds of hope for Sibiloi National Park [online]. Swara, No. 4., pp. 33-37. Available at: https://tuhat.helsinki.fi/portal/files/72572114/SWARA_2016_Sibiloi.pdf

Coppolillo, P. (2000). The landscape ecology of pastoral herding: spatial analysis of land use and livestock production in East Africa. Human Ecology, Vol. 28, No. 4, pp. 527-560.

Domínguez, P. (2010). Approche multidisciplinaire d’un système traditionnel de gestion des ressources naturelles communautaires: L’agdal pastoral du Yagour (Haut Atlas marocain). (PhD Thesis). Paris/Bellaterra: École des Hautes Études en Sciences Sociales / Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona, Available at : www.tdx.cat/bitstream/10803/79093/1/pdg1de1.pdf

Domínguez, P. and Benessaiah, N. (2015). Multi-agentive transformations of rural livelihoods in mountain ICCAs: The case of the decline of community-based management of natural resources in the Mesioui agdals (Morocco). Quaternary International, Vol.18 (November), pp. 1-11 doi :http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.quaint.2015.10.031

Dressler, W., Bram Büscher, B., Schoon, M., Brockington, D., Hayes, T., Kull, Ch. A., McCarthy, J., and Shrestha, K. (2010). From hope to crisis and back again? A critical history of the global CBNRM narrative. Environmental Conservation, Vol. 37, No. 1, pp. 5-15. doi:10.1017/S0376892910000044

Dudley, N., Mansourian, S., Suksuwan, S., 2008. Arguments for Protection: Protected areas and poverty reduction. Gland, Switzerland.

Fratkin, E. (2001). East African Pastoralism in Transition: Maasai, Boran, and Rendille Cases [online]. African Studies Review, Vol. 44, No. 3, pp. 1-25. Available at: http://www.smith.edu/anthro/documents/FratkinASRr-2-.pdf

Kothari, A., Camill, P., Brown, J., (2013) Conservation as if people mattered: policy and practice of community-based conservation. Conservation and Society 11, 1–15.

Kothari, A., 2015. Indigenous peoples’ and local community conserved territories and areas. Oryx 49, 13–14. doi:10.1017/S0030605314001008

Lane, C. (1990). Barabaig Natural Resource Management: Sustainable Land Use Under Threat of Destruction [online]. Discussion Paper, No. 12. United Nations Research Institute for Social Development. Available at:

http://www.unrisd.org/80256B3C005BCCF9/httpNetITFramePDF?ReadForm&parentunid=CAB206729493A99580256B67005B6057&parentdoctype=paper&netitpath=80256B3C005BCCF9/(httpAuxPages)/CAB206729493A99580256B67005B6057/$file/dp12.pdf

Lane, C. (1993) Past practices, present problems, future possibilities: Natural resource management in pastoral areas of Tanzania [online], In: Marcussen, H.S. (Ed.), Institutional Issues in Natural Resources Management. Occasional Paper, No. 9, Roskilde, International Development Studies, Roskilde University. Available at: http://rossy.ruc.dk/ojs/index.php/ocpa/article/view/4116

Lane, C., (1994). Pasture lost: Alienation in Barabaig land in the context of land policy and legislation in Tanzania [online]. Nomadic Peoples, No. 34/35, pp. 81-94. Available at: http://cnp.nonuniv.ox.ac.uk/pdf/NP_journal_back_issues/Pastures_lost_C_Lane.pdf

Leeuw, P. and Tothill, J. (1990). The concept of rangeland carrying capacity in sub-saharan Africa – myth or reality [online]. Land Degradation and Rehabilitation. Paper No. 29b. Available at: http://www.odi.org/sites/odi.org.uk/files/odi-assets/publications-opinion-files/5357.pdf

Liebmann, B., Hoerling, M., Funk, Ch., Blade, I., Dole, R., Xiaowei, D., Region, Ph., and Eischeid, J. (2014). Understanding Recent Eastern Horn of Africa Rainfall Variability and Change. Journal of Climate, Vol. 27. American Meteorological Society. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1175/JCLI-D-13-00714.1

Little, P. (1996). Pastoralism, biodiversity and the shaping of savanna landscapes in East Africa. Africa: The Journal of the International African Institute, Vol. 66, No. 1, pp. 37-51. doi: https://doi.org/10.2307/1161510

McCabe, T. and Ellis, J. (1987). Beating the Odds in Arid Africa [online]. Natural History, Vol. 96, No. 10, pp. 32–41. Available at: http://www3.gettysburg.edu/~dperry/Class%20Readings%20Scanned%20Documents/Intro/McCabe.pdf

McPeak, J. (2005). Individual and collective rationality in pastoral production: evidence from northern Kenya. Human Ecology, Vol. 33, No. 2, pp. 171-197. doi: 10.1007/s10745-005-2431-Y

Merino L. (2004). Conservación o deterioro. El impacto de las políticas públicas en las instituciones comunitarias y en las prácticas de uso de los bosques en México [online].México, D.F.: Secretaría de Medio Ambiente y Recursos Naturales. Instituto Nacional de Ecología. Available at http://www2.inecc.gob.mx/publicaciones/download/428.pdf

Moreno Arriba, J. (2013). La gestión comunitaria de recursos naturales, agrosilvopastoriles y pesqueros en la Sierra de Santa Marta, Veracruz, México: ¿una alternativa posible al discurso desarrollista y a la globalización capitalista? [online]. Universitas Humanística No. 75, pp. 189-217. Available at: http://revistas.javeriana.edu.co/index.php/univhumanistica/article/view/3846

Nkonya, L. (2006). Drinking from own cistern: customary institutions and their impacts on rural water management in Tanzania. (PhD Thesis). Manhattan: Kansas State University. Available at: http://krex.k-state.edu/dspace/handle/2097/178

Orindi, V. and Murray, L. (2005). Adapting to climate change in East Africa: a strategic approach [online]. Gatekeeper series, No. 117. London: Institute for Environment and Development. Available at: http://pubs.iied.org/pdfs/9544IIED.pdf

Ostrom, E. (1990). Governing the commons: The Evolution of Institutions for Collective Action. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Potkanski, T. (1994) Property concepts, herding patterns and management of natural resources among the Ngorongoro and Salei Maasai of Tanzania. International Institute for Environment and Development. Drylands Programme. London.

Robinson, L. (2009). A complex-systems approach to pastoral commons. Human Ecology, No. 37, pp. 441-451.doi: 10.1007/s10745-009-9253-2

Roe, D., Nelson, F. & Sandbroock, C. (2009). Community management of natural resources in Africa: Impacts, experiences and future directions [online]. Natural Resource Issues No. 18, London: International Institute for Environment and Development. Available at http://pubs.iied.org/pdfs/17503IIED.pdf

Sagawa, T. (2010). Automatic rifles and social order amongst the Daasanach of conflict-ridden East Africa. Nomadic People, Vol. 14, No. 1, pp. 87-109. doi: 10.3167/np.2010.140106

Tari, D. and Pattison, J. (2014). Evolving Customary Institutions in the Drylands: An opportunity for devolved natural resource governance in Kenya? [online]. IIED Issue Paper. London: International Institute for Environment and Development. Available at: http://pubs.iied.org/pdfs/10076IIED.pdf

Villamor, G. B., and Badmos, B. K. (2015). Grazing game: a learning tool for adaptive management in response to climate variability in semiarid areas of Ghana. Ecology and Society, Vol. 21, No. 1. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.5751/ES-08139-210139

Wilson, M., G. (1952). The Tatoga of Tanganyika. Tanganyika notes and records, No. 33.