The Journey towards Enhanced Quality of Basic Education in Kenya: Challenges and Policy Suggestions

David M. Mulwa

School of Education, Machakos University

Abstract

Kenya is a signatory to the 2015 United Nations Sustainable Development Goals. The fourth goal focuses on provision of quality and inclusive education. The government of Kenya has made some reforms in education both at the basic and higher education sector which is geared towards the provision of quality and inclusive education. The context-input-process and outcome educational quality indicators point to a worrying trend towards enhanced and sustainable quality of basic education. By the use of secondary sources, the study will outline the system wide and school challenges hindering enhanced quality of education. The system level challenges to be highlighted include the demographic, social and economic context of education, financial and human resources invested in education, access to education, participation and progression. The study will also concern itself with transition from school to employment, and student achievement and social and labour market outcomes. At the school level, the study will delimit itself to community involvement, financial and human resources utilization, achievement policy and educational leadership. Others will be school climate, efficient use of time, opportunity for learners to learn and teachers’ ratings by both pupils and peers. The study will make policy suggestions to address these challenges.

Key Words: Basic Education, Quality Indicators, Educational Challenges, policy

Introduction

Indicators tend to be classified depending on whether they reflect the means, the process, or the end in achieving the objective of a particular set of development policies, programs or projects. Good evaluation indicators should have an appropriate balance between different types of indicators that can establish the link between means and ends. Prevailing classifications of indicators are roughly similar, though some important differences exist. For the purpose of this paper, education quality indicators will be categorized as context, input, process or outcome indicators.

Context indicators: (defined at the level of national education systems) refer to characteristics of the society at large and structural characteristics of national education systems. Examples include demographics; e.g. the relative size of the school-age population; basic financial and economic context; e.g. the GDP per capita; and education goals and standards by level of education; e.g. higher completion rates. Others are more equitable distribution of university graduates and the structure of schools in the country.

Input indicators at system levels refer to financial and human resources invested in education. These include aspects such as expenditure per student, expenditure on Research and Development in Education; and the percentage of the total labour force employed in Education. Others are pupil teacher ratios per education level and characteristics of the stock of “human resources”, in terms of age, gender, experience, qualifications and salaries of teachers.

Process indicators at system level are characteristics of the learning environment and the organization of schools that are either defined at system level or based on aggregated data collected at lower levels. These include the pattern of centralization/decentralization or the “functional decentralization” specified as the proportion of decisions taken in a particular domain that is taken by a particular administrative level. Also includes priorities in the intended curriculum per education level, expressed, for example, as the teaching time per subject. Others include the priorities in the education reform agenda, expressed, for example as the proportion of the total education budget to specific reform programs and also investments and structural arrangements for system level monitoring and evaluation at a given point in time.

Output or outcome indicators at system level refer to statistics on access and participation, attainment statistics and aggregated data on educational achievement. These include participation rates in the various education levels (primary, secondary and tertiary) and progression through the education system, expressed for example of the proportion of students that gets a diploma in the minimum formal time that is available for a program. Others are drop-out rates at various levels of the education system and the average achievement in basic curricular domains, for example in subjects like mathematics, science, literacy, measured at the end of primary and/or secondary school;

Basic Education Demographics in Kenya

The Ministry of Education, Science and Technology (2014) has provided data for enrolment at the various levels of education between the years 2009 to 2014 as shown in the tables below

Table 1.0: Enrolment at Basic Education Institution in Kenya (in ‘000)

| Primary | 2009 | 2010 | 2011 | 2012 | 2013 | 2014 |

| Boys | 4772.8 | 4789.8 | 4887.3 | 4972.7 | 5019.7 | 5052.4 |

| Girls | 4460.7 | 4563.1 | 4673.7 | 4784.9 | 4837.9 | 4898.4 |

| Total | 9183.5 | 9352.8 | 9561.1 | 9757.6 | 9857.6 | 9950.7 |

| Parity index: Girls/Boys | 0.94 | 0.95 | 0.96 | 0.96 | 0.96 | 0.97 |

| Secondary | ||||||

| Boys | 787.9 | 885.5 | 948.7 | 1019.0 | 1127.7 | 1202.3 |

| Girls | 684.7 | 767.8 | 819.0 | 895.8 | 976.6 | 1107.6 |

| Parity Index: Girls/Boys | 0.87 | 0.87 | 0.86 | 0.88 | 0.87 | 0.92 |

Source: Ministry of Education (2014)

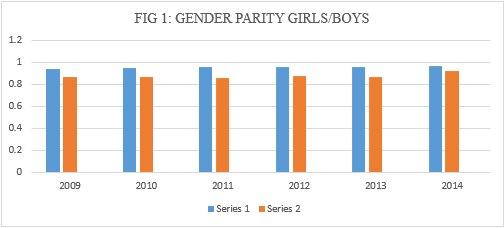

From the table 1.0 above, it is clear that the enrolment in both primary and secondary schools has been on an upward trend. The gender parity has been minimally on the increase, however the gender parity index in secondary schools is lower than in primary schools. This implies there is quite a significant number of girls who do not transit to secondary schools hence not completing the basic education cycle. This may be attributed to backward cultural practices such as female genital mutilation and early marriage in some Kenyan communities which affect the access of education by the girl child. This is likely in turn to affect the quality of education.

Within the same period, the schooling profile indicators for some selected classes was as shown in table 2.

Table 2.0: School Profile Indicators

| 2009 | 2010 | 2011 | 2012 | 2013 | 2014 | |

| Standard One | 112.4% | 109.7 | 107.8 | 105.8 | 104.3 | 102.1 |

| Access Standard 6 | 95.0 | 93.0 | 97.8% | 97.2% | 102.2% | 100.2% |

| Access standard 8 | 86.5% | 84.8% | 83.3% | 81.7% | 80.0% | 79.3% |

| Promotion Rate (Std Eight to Form One) | 57.0 | 59.2 | 60.1 | 69.5 | 75 | |

| Transition Rate( Primary to Secondary) | 55.0 | 61.0 | 63.5 | 64.5 | 74.7 | 79.6 |

Source: Ministry of Education (2014)

From the Table 2.0, it is clear that the numbers that joined standard one within the indicated five year period was more than the number that should have joined standard one then. This may be as a result of either underage or overage learners joining standard one or even repeaters or drop-outs who come back to school after several years. Those who have access to standard eight level for the five year period is less than 100% meaning that a number may have dropped out along the way due to either lack of opportunities or even repeated. Though the transition rate has been on the increase within the five year period, it is less than 100%. There is therefore a need for the government to come up with strategies that will ensure 100% transition. The retention rate within primary school has been on the increase attaining a maximum of 77.7% in the year 2014. In secondary school, the retention rate has been erratic with a minimum of 70.3% in 2010 and a maximum of 86.7% in 2013. This implies that there is need for the government to come up with policies that will ensure 100% at the secondary school level.

Socio-Economic Context of Basic Education in Kenya

Kenya attained her independence in 1963. The Kenyan economy is mainly agricultural based with cash crops such as tea and coffee being the main source of foreign exchange earner. In the Eastern African region, Kenya is the biggest economy, however other countries such as Rwanda and Tanzania have faster growing economies. The 2008 World Bank figures indicate that between 2005 and 2007 the economy grew from 5.5% to 6.5% after years of economic decline in the 1980s and 1990s (“Kenya – Data and Statistics,” 2008). This decline was the result of inappropriate policies, inadequate credit, and poor international terms of trade. The Gross Domestic Product (GDP) growth in 2006 was estimated at 6.1%. In contrast, the GDP in 2003 was $12.7 billion with an annual growth rate of 5.8% in 2005, and a per capita income of $471 (Human Development Reports – Kenya 2007/2008 Report, 2008; Kenya Education Sector Support Project, 2006; UNICEF, 2008). Kenya enjoys major achievement in education across all levels compared to other countries within the region. The current population of the country is estimated at 48 million with an annual population growth rate of 2.3% (CIA World Fact Book – Kenya, 2017; UNESCO Institute for Statistics, 2008b; The World Health Report – Kenya, 2008). UNESCO reports also indicate that of the total population, 60% are youth under the age of 30 years. The World Health Organization (WHO) and the United Nations Development Program (UNDP) Human Development Reports estimated the life expectancy at birth to be about 50% to 52% in 2005. The figures from UNESCO and UNICEF also show that the adult literacy rate for age 15 and older for between 1995 and 2005 was 73.6%, reasonably higher than that of many countries in Africa. The combined gross enrolment ratio for primary, secondary and tertiary education in 2005 was 60.6% with the government allocating 29.2% of the budget to education (Bunyi, 2006; UNESCO, 2008c)

Financial and Human Resource Invested in Education

According to the Economic Survey (2014) the MoEST’s total expenditure was expected to grow by 17.2 per cent from KSh 260.1 billion in 2012/13 to KSh 304.9 billion in 2013/14, and the total recurrent expenditure was expected to increase by 11.2 per cent to KSh 259.1 billion in 2013/14 from KSh 233.1 billion in 2012/13(KNBS, 2014). Recurrent budget on pre-primary education dropped significantly mainly due to transfer of pre-primary education function to the County Governments. The recurrent expenditure on university education was expected to increase by 10.4 per cent from KSh 42.4 billion in 2012/13 to KSh 46.8 billion in 2013/14 while that on higher education support services was expected to increase by 23.5 per cent to stand at KSh 6.2 billion in 2013/14. The increase may partly be attributed to an increase in the number of public universities to 31 in 2017 and salary awards for university staff. This is likely to rise during the 2017/2018 fiscal if the salary agitation by university lecturers and other staff is honoured. The Ministry’s total development grew by 41.9 percent from KSh 27.0 billion in 2012/13 to KSh.38.3 billion in 2013/14. Development expenditure on primary education grew considerably from KSh 330.0 million in 2012/13 to KSh 16.1 billion in 2013/14. The increase may be attributed to GOK’s pledge to supply all class one pupils in public schools with one laptop each through the one laptop per child project and the required infrastructure and capacity building for teachers.

Access, Relevance and Equity in Basic Education

The GOK introduced Free Primary Education in 2003 and Free Day Secondary Education in 2008. The objectives of these programmes were to increase access, quality, equity and relevance in basic education and to cushion poor households by abolishing school fees. The partnership between the development partners and government led to increased enrolment rates and retention of learners in schools. In evaluating UPE progress various indicators to determine achievement have been used and are explained below. Trends in Primary enrolment grew from 6.1 million in 2000 to 7.4 million in 2004, to 10.2 million in 2013. The steady increase, especially since 2003, can be partly attributed to strategies put in place by MoEST such as the free primary education and the school infrastructure expansion.

The GER increased from 88.7percent in 2000 to 119.6 percent in 2013, indicating enrolment of either under-age or over-age pupils or both in the system. The NER has been rising steadily since 2000 reaching 95.9 percent in 2013 against a target of 90 percent by 2010. However, an analysis of geographic and gender trends shows unsatisfactory enrolment levels. For example, NER in the counties of the North Eastern region was 40.3 percent against a national average of 91.4 percent in 2010. In general, the NER for boys was higher than that of girls in all Counties except Central Kenya. Development partners have supplemented government efforts towards enhancing access, retention and equity in education especially in areas where the GER and NER are lower than the national average. The Gross Enrolment Rate (GER) shows the general level of participation in a given level of education. It indicates the capacity of the education system to enroll pupils of a particular age group at a specific level of education and is complementary indicator to net enrolment rates (NER) by indicating the extent of over-aged and under-aged enrolment. GER can be over 100 percent due to the inclusion of over-aged and under-aged pupils/students because of early or late entrants, and grade repetition. NER show the extent of participation in a given level of education of children and youths belonging to the official age group corresponding to the given level of education. This is a very important indicator in measuring rates of access to education. Since the introduction of Free Primary Education in 2003, the GER has remained above 100.0 per cent, indicating enrolment of over-age and under-age pupils. In 2000, the primary completion rate was 57.7 percent (60.2 boys, 55.3 for girls). By 2013 it had increased to 81.8 percent (80.3 boys and 78.8 girls). Since the introduction of FPE in 2003, the pupil completion rate has been fluctuating between 57.2 percent and 83.2 percent. During this period 2003 – 2009, the pupil completion rate was just below the third quartile (75.0%). After 2009 it went above the third quartile. This remarkable achievement in completion rate can be attributed to increased access to basic education due to infrastructure development and policy shift favoring the promotion of girl education.

Transition from Primary to Secondary

In terms of financial resources, a total of Ksh 85,955,498,783.55 billion has been spent on the program through purchasing instructional materials, as well as general-purpose expenses/recurrent expenditures through a capitation grant of Ksh 1,020 per child in 77,532 public schools; 273 Mobile schools and 1,439 NFE since FDSE was initiated in 2008 (MoE, 2014) . Ministry of education further reported that despite the numerous achievements made by the free primary education initiative, 1.01 Million children were still out of school (GMR, 2013/4). The introduction of free day secondary education has also seen an increase in the transition rate, surpassing the national target of 70 percent of 2008 to stand at 76.6 (74.6 boys and 78.6 girls) in 2012 (World Bank, 2012). The capitation grant is Ksh 20,000 per student per annum, covering tuition and general-purpose expenses. Parents cater for boarding expenses, lunches, uniform and other development expenses. Trends in FDSE Capitation (2008 – 2014) Up to the financial year 2009/2010, MoEST disbursed Ksh 55,540,140,323 billion to 1,605,364 students in 6,009 schools in support of this programme (MoE, 2014). Free secondary education provision led to urgent need for more classrooms to accommodate more students who were transiting from primary level from primary level. Other programmes under FDSE include the general expansion of national schools to allow more students transiting from primary schools. Initially there were 18 national schools. For these schools to accommodate more students, a plan was put in place to upgrade them whereby they were given Ksh 48 Million to expand infrastructure, especially classrooms and laboratories so as to improve access (KNBS, 2014). This translates to Ksh 864 million per school. In 2011/12, 2012/13, 2013/14 FY another 30 schools were upgraded to national level with each getting Ksh 25 million to improve infrastructure (MoE, 2014). This translates to Ksh 75 billion. These funds were disbursed in three tranches between 2012/2013 FY to 2013/2014 FY. In the financial year that is 2014/2015 FY another 27 schools were to be upgraded to the national level where another Ksh 25,000,000.00 was to be disbursed to each school to upgrade their infrastructure to improve access. Sustained high level of investment in the education sector resulted in tremendous achievements in terms of access, transition, retention and quality in education. The transition rate from primary to secondary school has increased from 64.1 (61.3boys and 67.3 girls) in 2009 to 76.6 (74.6 boys; 78.6 girls) in 2012. This can be attributed to the government initiatives such as the Free Day Secondary Education programme which has expanded access to secondary education. Previously, user fees and levies hindered many learners from accessing secondary education due to the poverty level of learners mostly in the marginalized areas such as ASAL’s, urban informal settlements among others. The government is now geared towards 100% transition. However, teacher shortage has been a hindrance to this. In the year 2018, primary school shad a shortage of 40972 teachers while secondary schools had a short of 63849(TSC, 2018).

Recommendations

Policy Suggestions

In order to achieve a gender parity of 1.0 both at the primary and secondary school level, the government should sensitize the public and where possible enforce policies in support of the girl-child education. These may include total ban on female genital mutilation and early marriages, readmission of girls back to schools after teenage pregnancy, enhance the provision of sanitary pads in both primary and secondary schools. Although education is a basic right as stipulated in the Kenya Constitution 2010, there should be emphasis on the psychologically supported school age in order to avoid cases of over-age and under-age pupils in schools which is likely to lead to wastage in forms of drop-outs, repetition and poor school performance.

The transition rate from primary school to secondary may be high in certain regions and very low in certain marginalized regions. Unless the government formulates and implements appropriate strategies especially among the marginalized communities, it may not be easy to achieve 100% transition as it is anticipated. Though the government has made very positive efforts towards FDSE and FPE, there are need to diversify the sources of government revenue in order to create adequate financial resources that can be allocated to education and other competing sectors such as health and security.

Reference

Bunyi, G. W. (2006). Real Options for Literacy policy and practice in Kenya. PARIS: UNESCO

Central Bureau of Statistics (2002). Analytical Report on Education, Volume VIII. NAIROBI: KNBS

MoEST (2014). Basic Education Statistical Booklet. NAIROBI: UNICEF

Republic of Kenya (2008). Kenya national Human Development Report (2007/2008). NAIROBI: UNDP

Schreens, J.; Luyten, H.; Van raven, J. (Eds) (2011). Perspectives on Educational quality. Illustrative outcomes on Primary and Secondary Schooling in Netherlands. http://www.springer.com/978-94-007-0925-6

Teachers’ Service Commission (2018). Teaching Staff Data. Nairobi. TSC

UNESCO (2009). Education Indicators; Technical Guidelines. PARIS: UNESCO

UNESCO (2017). Sustainable Development Goals. PARIS: UNESCO Institute for Statistics

World Bank (2014). Kenya-Data and Statistics. Worldbank.org/archive/website01259/WEB/O- MEN-4.HTM

KNBS (2014). Economic Survey. Nairobi: KNBS