The Doomed Future: An Analysis of The Impact of ‘Muguka’ Abuse on University Students’ Academic Performance: A Case of Machakos and Kitui Counties, Kenya

Kimiti Richard Peter,

Graduate School, Machakos University

Email: prickimiti@gmail.com

Abstract

The problem of miraa (khat) abuse and its derivatives has been an area of concern in Kenya in the last decade. The previous studies carried out in this area revealed that the abuse of muguka, a derivative of miraa has been on the increase at the university level in Kenya. The purpose of the study was to investigate the impact of muguka abuse among university students in Machakos and Kitui Counties. Specifically, the study was set to establish the prevalence of muguka chewing at the university level according to gender and locality of students’ residence in Kenyan universities, to establish the relationship between muguka abuse and students’ academic performance and to find out the challenges faced by university students abusing muguka. The study used descriptive survey design. Stratified and simple random sampling techniques were used in the study. The sampling matrix comprised of 400 respondents; 344 students, 30 lecturers, 20 Heads of Departments and 6 student counselors. The study used two research instruments; a questionnaire and an interview. The data was analyzed using measures of central tendency. The findings of the study were; the prevalence of muguka abuse according to gender was male students 42.94% and female students 7.07% respectively. The students residing outside the university hostels had a prevalence of 45.17% whereas those staying in the university hostels had a prevalence of 35.50%. The students abusing muguka faced variety of problems; poor academic performance poor class attendance and indiscipline problems. The study recommends that university managements should promote primary prevention of muguka abuse through strengthening the Counseling departments.

Key words: abuse, academic performance, challenges, prevalence

Introduction

The abuse of drugs among university students has been reported to be on the increase since 2000 according statistics at NACADA (NACADA, 2001). This problem was predominant in the developed countries from 1950 up to-date (Johnston, 2015). In a study on causes of drug abuse among teenagers in Canada, Carter & Mason (1997) revealed that majority (79%) of the university student’s abused one drug or a combination of drugs such as cocaine, heroin tobacco, alcohol and Marijuana. Studies also carried out in Britain show that the abuse of bhang, alcohol, heroin, cocaine and miraa has been associated with the youth and in particularly university students since 1950 (Elizabeth, Susan, & Suman, 2003).

In most sub-Saharan countries, a similar trend of drug abuse has also been reported in various studies; medical drugs, inhalants, cocaine, heroin tobacco, alcohol and marijuana (Nnaji, 2000) The Kenyan situation about drug abuse reports comparable results (Oketch, 2008). Kombo (2006) noted that abuse of miraa and its derivatives is increasingly becoming a major problem among university students in Kenya.

The university students usually abuse drugs due to a variety of reasons: rebel against authority such as the university administration or parents; inflict physical pain on oneself and for relaxation (Anderson, 1998). According to Muya (2014), students also abuse drugs because of excessive pressure from lectures and parents on academic performance, peer influence and especially when the first year students join wrong and run away from the reality when life seems to be unbearable. Ndetei (2002) further notes that university students abuse drugs due to lack of proper role models at school and also the lack of effective counselling structures. positive leisure activities.

Research Problem

Despite the efforts made by the government of Kenya to wipe out the problem of Muguka chewing among university students, recent findings indicate that the chewing of Muguka is still on the increase at the university school level in Kenya (Mueke, 2014). The prevalence of muguka abuse at the national level among university students in 2011 was 37%. In 2012, it was 40.6%, whereas in 2016, it was 41.4%. The prevalence according to the information documented by the Ministry of Education for the years: 2013, 2014 and 2015 was 41.8%, 42.5% and 42.9% respectively (NACADA, 2016). The data presented above shows that the prevalence of muguka abuse at the national level has been going upward.

In Machakos County, information documented at the County Education Office indicates an upward trend on the prevalence of muguka abuse at the university level. The information shows that 41.5% university students abused muguka in 2013, while the prevalence rose to 41.2% and 43.7% in the years 2014 and 2015 respectively (Machakos County Education Registry,2016). In the same period, the prevalence abuse of muguka abuse among university students in Kitui County was 41.3%, 41.7% and 42.8% respectively (Kitui County Education Registry, 2016). The problem of the study was therefore to investigate the impact of muguka abuse among university students in Machakos and Kitui Counties

Limitations of the Study

This study was limited by the intervening variables related to the characteristics of the universities selected for this study only. These included the status of each university school (provincial or district) and the school’s resource base. The study was also limited to lecturer-related variables; experience in university life and personal competency on matters related to drug abuse among the university students. Student’s knowledge on muguka abuse could also have influenced their responses in the questionnaire. Another limitation to the study was related to sample size. Specifically the study was affected by the intervening variable of mortality rate where some respondents of the study returned their questionnaires partially filled. The effects of such variables were likely to have affected the results of this study.

Delimitations of the Study

This study delimited itself to public universities in Machakos and Kitui Counties, Kenya. Preferably, the universities sampled for the study should have been drawn from all counties in Kenya. However, this was not possible due to financial and time restraints. This study also narrowed itself to second and fourth year students and lecturers in public two public universities in Machakos and Kitui Counties. Thus the current study was confined to the variables that were related to muguka abuse. Once more, this choice was taken due the financial and time constraints.

Methodology of Research

The study used both qualitative and quantitative methodologies; however, quantitative methods were prioritized. The study used descriptive survey design. The design was applied since a large numbers of respondents were targeted to give their opinions and thoughts and even justify their response. The survey adopted a cross-sectional design and used students, lecturers, Heads of Departments and student counsellors simultaneously in the study.

Sample of Research

The target population of this study comprised of approximately, 15200 students, 350 lecturers, 60 Heads of Departments and 10 student counsellors in Machakos and Kitui Counties. The subjects of the study were drawn from two purposively selected public universities. A sample of 400 respondents was selected through stratified and simple random sampling techniques. The sampling matrix comprised of 400 respondents; 344 students, 30 lecturers, 20 Heads of Departments and 6 student counselors.

Data Collection Tools

The study utilized two research instruments: a questionnaires and an interview schedule. The validity and reliability of the research instruments was established by piloting the instruments in two public universities in Nairobi County. The items in the research instruments were improved after the pilot study. The reliability of the research instruments was determined through the test-re-test correlation formula. The reliability coefficient for the instruments was: Students’ Questionnaire (0.83), Lecturers’ Questionnaire (0.74) and Head of Departments Questionnaire (0.87).

Data Analysis

The data collected was analyzed using frequencies, percentages, mean and mode.

The data analyzed was categorized and presented as follows:

- Prevalence of muguka abuse at the university level according to gender and locality of students’ residence in Kenyan universities.

- Relationship between muguka abuse and students’ academic performance.

- Challenges faced by university students abusing muguka.

Results

Prevalence of Muguka Abuse at University Level According to Gender and Locality of Students’ Residence in Kenyan Universities

- a) Prevalence According to Gender of students.

The subjects of the study were asked to state the prevalence rate of muguka abuse among university students according to gender parity. The findings from the student respondents showed that the computed prevalence rate for muguka abuse among the male students was 42.94%. On the other hand, the calculated mean for the prevalence rate of muguka among the female students was 7.07%. In terms of group rating, the modal class for the muguka abuse was 41-50% for male students whereas that for the female ones was 1-10%. This means that more male students abused muguka as compared to their female colleagues. A summary of the study findings on prevalence rate for muguka abuse in the universities selected for the study according to gender is shown in the Table 1

Table 1: Prevalence of Muguka Abuse According to Gender of University Students According to Student Respondents

|

Gender |

Class |

Frequency(f) |

Mid point(x) |

fx |

Mean |

|

Male |

1-10 |

1 |

5.5 |

5.5 |

42.94 |

|

11-20 |

5 |

15.5 |

77.5 |

||

|

21-30 |

21 |

25.5 |

535.5 |

||

|

31-40 |

27 |

35.5 |

958.5 |

||

|

41-50 |

290 |

45.5 |

13195 |

||

|

Σf |

344 |

|

Σfx=14772 |

||

|

Female |

1-10 |

323 |

5.5 |

1776.5 |

7.07 |

|

11-20 |

4 |

15.5 |

62 |

||

|

21-30 |

5 |

25.5 |

127.5 |

||

|

31-40 |

8 |

35.5 |

284 |

||

|

41-50 |

4 |

45.5 |

182 |

||

|

Σf |

344 |

|

Σfx2432 |

The lecturer respondents reported a similar configuration of the prevalence of muguka abuse. For instance, they stated that 43.2% male students had abused muguka. Five (62.5%) of student counselor interviewees reported that cases of muguka abuse at the university level were increasingly becoming a vice among students. There were only three student counselor interviewees who reported a low prevalence rate of muguka abuse among students in their universities. However, an interview with other lecturers from the same universities revealed that the three student counselor interviewees had only served for a few months at their universities before the study was carried out and hence their opinions were not reliable. The data collected from the Heads of Departments’ respondents showed that both male and female students were vulnerable to muguka abuse.

- b) Prevalence of Muguka Abuse According to Locality of Students’ Residence

The study also aimed at establishing the prevalence of muguka abuse according to the locality of students’ residence. The data collected according 15(75.00%) Heads od Departments sampled for the study showed that most of the university students were non-residents (living outside the university) whereas the rest 5(25.00%) were residential students. The prevalence rate of muguka abuse was higher among the non-residential students at 76.67% compared to that of the residential ones (23.33%) as reported by the student respondents. A summary of the responses by the lecturer respondents is shown in Table 2

Table 2: Locality of University Students’ Residence in Machakos and Kitui Counties

According to the Lecturer Respondents

|

Locality |

Class |

Frequency(f) |

Mid point(x) |

fx |

Mean |

|

Residential |

1-10 |

3 |

5.5 |

16.5 |

35.50 |

|

11-20 |

2 |

15.5 |

31 |

||

|

21-30 |

4 |

25.5 |

102 |

||

|

31-40 |

4 |

35.5 |

142 |

||

|

41-50 |

17 |

45.5 |

773.5 |

||

|

Σf |

30 |

|

Σfx=1065 |

||

|

Non-Residential |

1-10 |

3 |

5.5 |

16.5 |

45.17 |

|

11-20 |

2 |

15.5 |

31 |

||

|

21-30 |

1 |

25.5 |

25.5 |

||

|

31-40 |

0 |

35.5 |

0 |

||

|

41-50 |

5 |

45.5 |

227.5 |

||

|

51-60 |

19 |

55.5 |

1054.5 |

||

|

Σf |

30 |

|

Σfx 1355 |

Table 2 shows that the computed mean for muguka abuse prevalence rate among the non-residential students was 45.17% whereas that for the residential ones was 35.5%. The modal class for the prevalence rate was 41-50% and 51-60% among residential and non-residential students respectively. This suggests that the students living outside university hostels were more likely to abuse muguka compared to those living within the university hostels. The findings shown in table 2 were supported by those of the student counselors who said that majority cases they handled during guidance and counselling sessions on muguka abuse involved found among the non-residential students. This observation was linked to the fact that the non-residential students could easily access muguka on their way to and fro the university. The strict rules governing students living in the university hostels could also be isolated as deterrent to Muguka abuse among students. Interviews with some of the Heads of Departments confirmed the same trend of Muguka abuse among university students based on their areas of residence. For example, 11(55.00%) of the HOD interviewees suggested that non-residential students abused muguka whereas 9(45.00%) residential ones were also affected.

Relationship between Muguka Abuse and Students’ Academic Performance

The study also sought to establish whether there was a relationship between the abuse of Muguka and students’ academic performance. The findings of the study revealed that 35.00% HODs respondents suggested that the abuse of Muguka does not affect the students’ academic a performance. On the other hand 55.00% HODs agreed that abuse of Muguka could negative affected students’ academic performance. These results were supported by the lecturer respondents when 66.67% suggested that Muguka abuse affected students’ performance in their academic work. Similarly, 69.48% student respondents noted that the abuse of Muguka negatively affected their academic performance.

Table 3: Relationship between Muguka Abuse and students’ Academic Performance

|

Respondent |

Strongly Disagree |

Disagree |

Not Sure% |

Agree % |

Strongly Agree % |

Total |

|

HODs |

3(15.00) |

4(20.00) |

2(10.00) |

5(25.00) |

6(30.00) |

20(100%) |

|

Lecturers |

4(13.33) |

4(13.33) |

2(6.67) |

11(36.67) |

9(30.00) |

30(100) |

|

Students |

38(11.04) |

47(13.66) |

20(5.82) |

110(31.98) |

129(37.5) |

|

|

Student- Counsellors |

1(16.67) |

1(16.67) |

0(0.00) |

2(33.33) |

2(33.33) |

6(100) |

In addition, the findings of the study also revealed that 66.66% student counsellors agreed that the abuse of Muguka may negatively influence students’ academic performance.

Challenges Faced by University Students Abusing Muguka

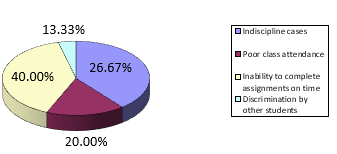

The teacher respondents were also asked to highlight the challenges faced by university students who abuse Muguka. A summary of their responses is given in Figure 1 below.

Figure 1: Challenges Faced by University Students Abusing Muguka

Figure 1 shows that 12 (40.00%) lecturer respondents revealed that students abusing muguka had a problem in completing their class assignments on time. Another 13.33% students abusing muguka were likely to be associated with indiscipline cases. Similarly the students abusing muguka were also discriminated by their classmates. Apart from the above challenges such students missed lectures from time as indicated by 20% of the lecturer respondents. These findings were further supported by the student counsellors who also revealed that 33% of the counselling cases they handled involved students who abused muguka. Another challenge faced by university students who abused muguka as highlighted by Heads of Department was that of missing marks. This was triggered by the students’ inability to register the units for every semester. In addition, such students had a myriad of personal problems as shown in the pictorial illustrations in page 10 and 11.

Discussion

As noted earlier in this section, the findings of the study revealed that the prevalence of muguka abuse among university students was influenced by one’s gender. This trend of Muguka abuse and other drugs according to gender parity is not new. Shafiq, Shah, Saleem, Siddiqi, Shaikh, Salahuddin & Naqvi (2006) in a study on prevalence of drug abuse among the Canadian university students reported that drug abuse was significantly related to gender. According to Shafiq et al (2006) the prevalence of drug abuse was higher among the male students compared to the female ones. The male youth were also found to have used several drugs by the time they were in second year. The female ones were introduced into drugs by their boyfriends towards the end of their studies. This finding proposed that male students were more susceptible to drug abuse as compared to their female colleagues. Similarly studies carried out by Kimiti (2011) and Smith (2001) showed that drug abuse prevalence is strongly influenced by gender due to the different cultural upbringing between male and female children.

Although the findings of this study suggested that muguka abuse was more prevalent among the non-residential students compared to those in living in university hostels, the results seemed to contradict those of a study carried by Nnaji(2000) which reported no significant correlation between drug abuse prevalence and the locality of a student’s in a study carried out on college students in Nigeria. According to Siringi & Waihenya (2001), the prevalence rate of muguka abuse among university students in Embu County, was significantly predisposed by the economic activities from the students’ home background. The universities with established rules and regulations were found to have a lower prevalence rate compared to those with more liberal rules and regulations. However, research findings of a study carried out in South Africa concurred with the findings of the current study when they reported that the prevalence of drug abuse was influenced by the locality of the residence (UNDP, 1994).

Although the findings of this study suggested that muguka abuse has negative effects on students’ academic performance, the results seemed contradict those of Mithamo (2004) when he reported miraa and its derivatives is not an addictive drug and consequently does not affect someone’s functions in any way. Similar sentiments were voiced by the former govern of Meru when campaigning against the ban of miraa exports to Britain as illustrated in the photo below;

Former Meru Governor Peter Munya chews miraa in Ntonyiri, Igembe North on June 8. A new study indicates miraa leads to poor academic performance (Mose Sammy, Standard 30th June2017)

However other studies carried out elsewhere tend to concur with the findings of the current study. Similarly research findings of a study carried out in Nigeria further agreed with the results of the current study when they reported that alcohol abuse was associated with academic retardation among university students Nnaji (2000). Thus the findings of the current study point out that muguka abuse have a long lasting impact on students’ academic performance.

The challenges associated with drug abuse have been underscored earlier in several studies not only in Kenya but across the globe (Bush, Kivlahan, McDonell, Fihn, & Bradley, 1998). According to Obot(1993) , Kilonzo (1992)and Chesang (2013), many deaths caused by road accidents among the youth are attributed to drug abuse. The abuse of Muguka is not an exception. The findings of the study carried out by WHO (2012) seemed to be in agreement with the findings of the current study it reported that Muguka abuse among university and college students had robbed Kenya a good number of untapped talents in the last one decade.

Conclusion

The findings of this study as reported and discussed in this section revealed that the prevalence rate of muguka abuse among university students in Machakos and Kitui Counties was higher among male students school compared female ones. It was also established that non-residential students had higher muguka abuse prevalence rate compared to the residential ones. The following are some of the challenges faced by university students abusing Muguka: inability to complete class assignments on time indiscipline cases, discrimination by their classmates, missing lectures, missing marks, inability to register the units for every semester and a myriad of personal.

References

Anderson, B.K. (1998). Drug Abuse among the American Teenagers. New York: Oxford University Press.

Bush, K., Kivlahan, D. R., McDonell, M. B., Fihn, S. D., & Bradley, K. A. (1998). The AUDIT alcohol consumption questions (AUDIT-C): an effective brief screening test for problem drinking. Archives of internal medicine, 158(16), 1789-1795.

Carter, C. & Mason, N. (1997). A Review of the Literature on the Cognitive Effects of Integrated Curriculum. Paper presented at the Annual Conference of the American Research Association, Chicago, March 24 – 28, 1997.

Chesang R. K.,(2013). Drug Abuse Among The Youth In Kenya, International Journal Of Scientific & Technology Research V2 , ISSUE 6, JUNE 2013 ISSN 2277 -8616 126 IJSTR©2013 www.ijstr.org

Emmanuel, F., Akhtar, S., &Rahbar, M. H. (2003). Factors associated with heroin addiction among male adults in Lahore, Pakistan. Journal of psychoactive drugs, 35(2), 219-226.

Elizabeth B. R., Susan L. D, and Suman A. R. (2003) Preventing Drug Use among Children and Adolescents: A Research –Based Guide for Parents, Educators, Geneva: ILO Publications

Gay, R.L. (1992). Educational Research: Competences for Analysis and Application. Ohio: Charles E. Merrill Publishing Company.

Johnston, K. (2015). Drug Use among American High School Students 1995-1997: Report Prepared by Institute of Social Research for National Institute on Drug Abuse. Maryland: D.H.H.S Publication.

Kilonzo, G. P. (1992). The Family and Substance abuse in the United Republic of Tanzania. Bulletin on Narcotics, Vol. XLVI (1):87-96.

Kimiti,R. P (2011). Teaching of the integrated topics on drug abuse as a strategy to eradicate drug abuse among secondary school students in Machakos District, Kenya, Unpublished PhD, Thesis, Kenyatta University, Kenya.

Kitui County Education office (2016). Annual Report on Secondary School Enrolment, 2(1), 20-24.

Kombo, D.K. (2006). Sociology of Education. Nairobi: Pauline’s Publication of Africa.

Kothari C.R. (2003) Research Methodology: Methods and Techniques. New Delhi: Vishwa Publishers.

Machakos County Education Registry (2016). Annual Report on University School Enrolment, 3(2), 14-15.

Mueke, J.M. (1998). Drug use and addiction among Kenyan school children. Unpublished Research findings, Kenya Institute of Education.

Munyoki, R. K. (2008). A study of the causes and effects of drug abuse among students in selected secondary schools in Embakasi division, Nairobi East District, Kenya. Unpublished M.E. D. Projects, University of Nairobi.

Mithamo, S. M. (ed.) (2004). Drug Demand Education: Education Programmeme, Trainers Reference Manual. Nairobi: Tribut Printers.

Muya, S. M. (1999). A Pilot Study Project on Preventive Education against Alcoholism and Drug Abuse. Nairobi: UNESCO Publications.

NACADA, (2001). Youth in Peril-Alcohol and Drug Abuse in Kenya. Nairobi: Government Printer.

NACADA (2016). A Study on Prevalence of Drug Abuse in Kenyan Institutions of Learning: The Daily Nation Newspaper. 13-15

Ndetei, J.P. (2002). School unrest in Kenyan Secondary Schools: A case study of Kyanguli Secondary School. Unpublished Government Report.

Nnaji, F.C., (2000) Appraisal of psychoactive substance use and psychological problems in the School students in Sokoto state, Nigeria. Proceedings of the year 2000 annual conference of the Association of Psychiatrists in Nigeria held at Federal Neuropsychiatric Hospital, Calabar, Nigeria

Obot, I.S. (1993). Epidemiology and Control of Substance abuse in Nigeria. Centre of Research and Information on Substance Abuse (CRISA), Jos, Nigeria.

Oketch, S. (2008). Understanding and Treating Drug Abuse. Nairobi: Queenex Holdings Ltd

Shafiq, M., Shah, Z., Saleem, A., Siddiqi, M. T., Shaikh, K. S., Salahuddin, F. F., & Naqvi, H. (2006). Perceptions of Pakistani medical students about drugs and alcohol: a questionnaire-based survey. Substance abuse treatment, prevention, and policy, 1(1), 31.

Siringi, S. & Waihenya, K. (2001). Drug abuse rife as government braces for narcotics war in Kenyan schools.

Smith, T.E. (2001). Alcohol Education and Pleasures of Drinking. Journal of Health Education, 8. (1) 17-19.

UNDP (1994). Africa Country Profiles, Africa Section, Demand Reduction. Vienna: UNDP Publications.

United Nations Organization, (2014). Drug Abuse Control Strategies. Geneva: UNO.

World Health Organization(2012). Alcohol Consumption and Alcohol related Problems: Development of National Policies and Programmes. Report on Technical Discussions of 35th World Health Assembly. Geneva: WHO