Harnessing Educational Technology to Stimulate Critical Thinking among Secondary School Learners for Sustainable Development in Kenya

1Johannes Njagi Njoka & 2Perminus Githui

Corresponding author: njokajohannes@gmail.com

1,2 Department of Psychology and CommunicationTechnology

Karatina University

Abstract

Critical thinking (CT) is an essential life skill that educators and mentors ought to equip learners with in order to enable attainment of Kenya’s vision 2030 and the sustainable development goals (SDGS). Psychologists and philosophers argue that critical thinking provides individuals with the mental ability to think inquire and interrogate issues in society which eliminates bias and blind acceptance of viewpoints. Individuals who are proficient in critical thinking are able to conduct strategic thinking, creative thinking as well as engaging in appropriate decision making and problem-solving processes. Individuals empowered with these competencies are characterized by the ability to adjust to diverse demands of their environment. The outcome is individuals who are highly employable, adaptable and inquisitive with a propensity to positively influence society with innovations and social re engineering of communities with ideas. There is an apparent disconnect between the expected role of education in fostering critical thinking and the real products of our education from secondary schools in Kenya. A study by Githui, Njoka and Mwenje (2017) established that the levels of critical thinking among secondary school learners in Nairobi and Nyeri Counties were disturbingly very low. This scenario implies that students’ mental abilities hardly perform beyond mere memorization of facts and information. Learners critically lack the abilities to synthesize, analyze and evaluate information. Such learners graduate from schools while weak or deficient in life skills necessary for effective living, work performance and inability to engage in activities of daily living in society. Unfortunately, educators in majority of learning institutions in Kenya lack the understanding of how educational technology can be harnessed to stimulate critical thinking skills among learners during teaching and learning processes. This is despite the fact that critical thinking can be infused in pedagogy across all disciplines without occasioning expensive curriculum reviews. This study seeks to provide insights and information to educators and policy makers on how educational technology can be harnessed to stimulate critical thinking among learners during the teaching and learning process for sustainable development in Kenya.

Key words: Critical thinking, creative thinking, pedagogy, educational technology, inquisitiveness

Introduction

The demands of life coupled with the complexity of our modern society continue to emphasize critical thinking as an essential life skill required of every individual in the contemporary times. The fundamental need to impart people with critical thinking skills is necessitated by diverse dynamics taking place in our contemporary society such as the rapid changes in technology, globalization and internationalization of labor and human capital requirements among other socio-economic changes. Nyonje and Kagwiria (2012) argued that the school being one of the greatest socializing agents in the shaping of personality of individuals has a very instrumental role in inculcating life skills such as critical thinking. The school years represents a vital stage in the development of individuals when large populations of children are prepared to participate in society as good citizens and as agents of development. Healy (1990) argued that critical minds were increasingly gaining status as society’s most valuable and sought after resource worthy of investing effort and time to cultivate. Scholars and policy makers argue that in order to produce students who are competitive globally, schools must churn out graduates who possess problem solving and critical thinking skills (Law & Kaufhold, 2009). Critical thinking skills is greatly emphasized as a fundamental life skill that every individual in society should acquire in order to promote sustainable development of their societies and nations.

Purpose of the Study

The purpose of the study was to assess the levels of critical thinking among learners in public secondary schools from Nyeri and Nairobi Counties in Kenya.

Objectives of the Study

The study was guided by the following objectives, to;

- Discuss how to harness instructional resources during pedagogy to stimulate critical thinking among learners for sustainable development in Kenya.

- Assess use of instructional techniques to promote critical thinking among learners in secondary schools in Kenya.

- Evaluate how assessment techniques are used in developing critical thinking among learners in secondary schools for sustainable development in Kenya.

Methodology

The study was guided by the social cognitive theory (SCT) propounded by Albert Bandura as its theoretical framework. Library review of secondary data was conducted to provide information on how to harness educational technology to stimulate critical thinking among secondary school learners in Kenya. An empirical study on critical thinking skills conducted from Nairobi and Nyeri counties is also presented in the study. Empirical study was based on the descriptive survey research design. Kothari (2004) states that descriptive studies enable researchers to collect data relating to a phenomenon and are devoid of any form of manipulation of the variables in the study. Additionally, a descriptive design makes it possible to collect data over a large population within a short time (Kothari, 2004). Target population for this study consisted of learners from public secondary schools from Nairobi and Nyeri Counties. Nairobi had 86 schools with an enrollment of 10,796 students, while Nyeri had 214 schools with 58,424 students ((MoEST, 2013; Nyeri County office, 2013). Thus the total number of learners in the two counties was 69, 220. The schools were stratified into three categories, namely; boys, girls, and co-educational (mixed) institutions.

Kothari (2011) asserts that a sample size of 10% of the target population is an adequate representation for a large population. Thus, a sampling index of 0.1(10%) was selected from the three categories of schools, which gave; 2 boys’ schools from each county and 2 and 3 girls’ schools from Nairobi and Nyeri Counties respectively. Further, 17 and 4 mixed secondary schools in Nyeri and Nairobi Counties were sampled, this gave a total of 30 schools for the study. Sampling tables by Krejicie and Morgan (1993) were used to determine the sample size, which yielded a sample of 376 respondents. Since the sampled respondents were distributed in the 30 sampled secondary schools, the number of students selected from each of the schools was 13. The sample size of the study is presented in Table 1. Data was collected using the Dindigal and Aminabhavi (2007) Psychosocial Competence Scale which was modified for the study. The responses of the students were used to work out a mean score which rated the learners’ critical thinking skills on a scale of 1 to 5. Students who attained a mean score below 3.0 were rated as having a low level of critical thinking skills, 3.0–3.9 represented a moderate level while mean scores that were above 4.0 were considered to exhibit a high level of the attribute. The Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS) version 20.0 was used to analyze data.

Table 1: Sample Size

|

Nairobi |

20 |

24 |

42 |

2 |

2 |

4 |

52 |

52 |

|

Nyeri |

19 |

25 |

170 |

2 |

3 |

17 |

137 |

150 |

|

Total |

39 |

59 |

212 |

4 |

5 |

21 |

189 |

202 |

Literature Review

Educational Technology and Critical Thinking

Educationists argue that harnessing educational technology to stimulate critical thinking among learners while in school is instrumental in empowering them with attitudes and abilities necessary for their active participation in the transformation of their societies. The term educational technology can be clearly understood by examining the major components of the concept, ‘technology in education’ and ‘technology of education.’

Technology of Education

The term ‘technology of education’ refers to application of theories and laws/rules in education for the purpose of improving the quality of education. Technology of education is a component of educational technology that embodies the use of systems approach to promote high quality education (Simiyu, 2000). Furthermore, this aspect of educational technology is concerned with the use of systematic and scientific procedures in educational practice (Maundu, Sambili & Muthwii, 2005). Simply put, technology of education refers to the application of the systems approach to educational enterprise. The cardinal concerns of technology of education involves empowering learners to perform activities such as; identification of educational problems, analyzing problems, setting objectives, suggesting solution strategies, synthesizing the processes, embarking on evaluation and providing feedback. These activities indicate the desired outcomes of critical thinking.

Gilkey and Howard (1977) define educational technology as a complex, integrated process involving people, procedures, ideas, devices and organizations, for analyzing problems and devising, implementing, evaluating and managing solutions to problems in all aspects of human learning. Mukwa (2015) argue that in educational technology, the solutions to problems take the form of all the learning resources that are designed, selected and utilized to bring about learning. In the educational sense, the resources are identified as messages, people, materials, devices, techniques and settings. This implies all the variables required in accomplishing effective communication. For critical thinking to be realized, learners must be actively involved in the teaching and learning processes by requiring them to apply their understanding as well as in manipulating the instructional resources used during instruction.

From these discussions, it is noted that a combination of the meaning of technology in education and technology of education provides an acceptable description of educational technology.

Psychological Basis of Educational Technology

As a discipline and in line with the dictates of technology of education, educational technology draws a lot from the field of psychology in general and psychology of learning in particular. The works of such psychologists as B. F. Skinner, Pressey and Watson greatly influenced the method and practice of educational technology (Coon, Mitterer, Brown, Malik, & Mckenzie, 2014). Indeed, the influence of the behaviourist psychologists mentioned above has far-reaching effect on educational technology (Mukwa, 2015). The process of inculcating learners with critical thinking skills demands careful application of psychological principles of learning and reinforcement as well as adopting child-centered learning strategies and learner involvement.

The works of B.F. Skinner in the production of the teaching machines led to massive involvement of educational technologists in the production of more sophisticated instructional resources. The behaviorists’ interest in research and experimentations in mastery learning based on the principle of individualization has metamorphosed into modern-day application of modular instructional packages as well as adoption of high technological-based distance education mode of information dissemination to a mass of populace (Otunga, Odero & Barasa, 2011). The works of the behaviorists led to theories such as reinforcement that has led to propagation of reward by the educational technology experts in their efforts at designing instructional packages.

Whether in live classroom teaching or mediated instructional process, an instructional designer knows that it is imperative to build an effective “reward” strategy. Thus, in computer-assisted designed program, such words like correct, right, good and splendid are used (Mukwa & Too 2001). Adherence of specialists in educational technology in the use of the principle of immediate knowledge of results (IKOR) was not unconnected to the work of the behaviorists or linguists. Because of this, rewards whether symbolic or not are usually provided immediately after a correct response. Psychological laws such as “readiness” which emphasize that students learn a task better and easier when they are mature for the task from psychological, physiological, and intellectual points of view, has been found applicable in the design of instructional packages by educational technologists. During the teaching and learning processes, teachers are expected to employ principles of educational psychology in ensuring learners are motivated and interested in what they learn especially critical thinking skills.

Philosophical Basis of Educational Technology

The definition of educational technology that has enjoyed general acceptability is that which defines it as “a systematic way of designing, planning, implementing and evaluating the total process of teaching and learning based on specific objectives using human and non-human elements together with application of communication theories to achieve predetermined objectives (Mukwa, 2015). In this sense, educational technology is defined as a systematic and scientific approach to identification of educational problems using human and non-human elements in the designing, planning, implementing and evaluating strategies aimed at a better performance of the educational system. By its very nature, educational technology is an eclectic discipline. By being eclectic is meant that the disciplines have elements of some other disciplines in it. The philosophical basis of educational technology stresses the need to involve learners in the learning process as well as ensuring learning activities and content reflect the developmental stages and interests of the child (Maundu, Sambili & Muthwii, 2005). Content learnt ought to be that which is within the mental level of the learner and has relevance to the needs of the society. In regard to life skills education, especially impartation of critical thinking skills, the values and abilities taught must be those that are relevant to the learner and the society.

In the contemporary times, employers are looking for employees who can think critically and produce results (Law & Kaufhold, 2009). Despite the emphasis on critical thinking as an educational outcome, majority of schools miss to inculcate critical thinking to their students. Failure to equip learners with critical thinking skills while in school results in the majority of the general public not being able to practice it at all (Mendelman , 2007). Hayes and Devitt (2008) observed that critical thinking strategies are not extensively developed or practiced during primary and secondary education due to the emphasis on rote learning which is motivated by the need to attain high academic scores in national examinations. Nyonje and Kagwiria (2012) report that in Kenya, life skills education has always been imparted through co-curriculum programs which include activities such as games, sports, clubs, societies, music, guidance and counseling. It is good to note that these activities are handled outside the classroom. In Kenya, life skills education was introduced as a core subject and allocated space and time in the school timetables in 2009. The government of Kenya through the ministry of education together with support from development partners has spent a lot of resources in the inception and implementation of life skills education in public schools since 2009. The Kenya Institute of Curriculum Development (KICD) has designed a life skills education curriculum which is being implemented by public schools across the country (Nyonje & Kagwiria, 2012). However, the subject continues to be taught as a non-examinable subject just like physical education (PE) subject, which implies that many teachers may not place a lot of importance on it during teaching and learning processes.

Use of Instructional technology to stimulate critical thinking skills

Instructional technology plays a pivotal role in the process of imparting life skills especially critical thinking skills among learners. Peron (2010) argues that during pedagogy, teachers face the unique challenge of trying to balance between the twin academic processes of helping learners to acquire content together with stimulating critical thinking. This phenomenon is attributed to instructional requirements that place undue emphasis on mastery of core subject matter and the strive to satisfy stakeholder expectations of assisting learners to pass examinations and attain quality mean scores to enable educational institutions to be ranked at the top. The emphasis of passing examinations as a fundamental educational outcome among learners has probably compromised the need to focus instructional acquisition of critical thinking skills. Matheny (2009) reported that majority of teachers in public schools have become so overly focused on their students attaining high grades in examinations that many sometimes end up teaching the test itself. Jenkins (2009) points out that when critical thinking skills are omitted from the educational process, society misses tremendous benefits. In particular, students lack critical thinking skills which inhibit their ability to respond appropriately to challenges that they may encounter in new and unfamiliar situations that are helpful to intellectual development. In agreement to this view, Tsui (2002) noted that critical thinking skills challenge what is typically assumed by others and encourages learners to recognize the importance of different perspectives in problem solving. Indeed, Willingham (2009) observed that development of critical thinking skills improves content uptake and retrieval through the concept of meaningful learning. Matheny (2009) argued that critical thinking skills and acquisition of content complement each other, adding that the idea of choosing between the two is a false dichotomy. Matheny further emphasized that instruction of critical thinking and core content should be designed to be delivered simultaneously.

McCollister and Sayler (2010) averred that critical thinking can be infused in lessons throughout all disciplines by utilizing in-depth questioning and evaluation of both the data and its sources. Having students track patterns in information stimulates them to look at the information as a process instead of simply information to be memorized and helps them develop skills of recognition and prediction. Evaluation of information helps students to learn appropriate procedures for utilizing credible information, as well as helping them to learn acceptable and appropriate ways to use discretion (McCollister & Sayler, 2010). These skills are helpful in reading, comprehension and problem-solving skills, all of which play an important role in standardized assessments (McCollister & Sayler, 2010). This deeper understanding allows the learners to better analyze the circumstances surrounding the occurrence and conflicting viewpoints about a phenomenon (Tsai, Chen, Chang & Chang, 2013).

Tsai, et al (2013) found that enhancement of critical thinking among students in science disciplines helped the students to better understand the scientific processes and also stimulated students to become more experimental and inquisitive of the diverse facets of the sciences. Knodt (2009) stated that innovative thinking is improved when the natural inquisitiveness that students bring to the learning process is inspired, affirmed, and cultivated. When given the opportunity to ask and explore openly, students acquire and blossom the critical thinking skills. Opportunity must be provided by the educator for students are to learn to be critical thinkers rather than passive dull thinkers. Opportunities must be provided for students to voice opinions and objections to topics rather than seek right or wrong answers. The brainstorming process is necessary to fuel the budding curiosity of the learner. Content knowledge is best taught using natural curiosity because there is an innate desire within every individual to learn by challenging traditional thinking patterns (Healy, 1990). Critical thinking, higher order thinking and problem solving make learning motivating, stimulating, and enjoyable (Jensen, 2005).

Experts have argued that effective teaching of critical thinking skills can be enhanced by having a more standard definition of what it entails (Choy & Cheah, 2009; Rowles, Morgan, Burns, & Merchant, 2013). This definition would allow educators at all grade levels to align the current curriculum with activities and lessons that help in cultivation of critical thinking among learners. In order to engage students in critical thinking, the teacher needs to act as a facilitator to give room for discussion and encourage a free thought process, as well as to encourage understanding that thinking critically does not always end with a right answer, but instead sometimes ends in more questions or differing evaluations of the theme being interrogated (Arend, 2009). The teacher’s role as facilitator also boosts a peer review process that helps students to learn appropriate responses to conflicting evaluations and opinions (Henderson-Hurley & Hurley, 2013).

Henderson-Hurley and Hurley (2013) suggested that the effort for more critical thinking is a holistic endeavor, which require cooperation among different departments, divisions, and classes. The development of critical thinking skills is not only applicable to core subjects such as reading, mathematics, language, arts, science, and social studies but cuts across the entire curriculum that learners are exposed to. This implies that every activity that learners encounter while in school should be structured in such a manner as to encourage and stimulate critical thinking. There is need for teachers to be conscious that core subjects, co-curricular activities together with the hidden curriculum in schools should all in an integrated and complementary way enable learners to cultivate and acquire critical thinking skills.

Kokkidou (2013) established that by challenging students to think critically, teachers were finding themselves thinking more critically about their subjects of expertise. Working to increase critical thinking of students has shown some promising results for both students and educators. The establishment of professional learning communities allows educators to think critically about the methods they use in teaching, and is a good starting point for ideas about inclusion of critical thinking skills in the classroom (Smith & Szymanski, 2013). Activities such as writing essays, debating and utilizing questions that adhere to higher order thinking in the Bloom’s taxonomy are examples of ways to engage students in critical thinking in the classroom (Smith & Szymanski, 2013). Educational technology involving collaborative group work is essential in enhancing critical thinking. Collaborative group work is the use of works to solve problems/questions in education (Snodgrass, 2011). Sadker and Sadker (2003) states that in an education that promotes critical thinking skills, learners are encouraged to interact with each other and develop social virtues such as cooperation and tolerance of different points of view.

Over emphasis on teaching content is a significant impediment to the teaching of critical thinking skills. Jenkins (2009) states that across all subjects, content should be taught by integrating critical thinking with the objective of teaching students to think. Engaging the brain through critical thinking and problem solving is much more beneficial than memorization of isolated facts (Matheny, 2009). Other barriers to the teaching of critical thinking include the class size, the amount of time allocated per lesson and teacher attitudes (Slavin, 2009). The traditional pedagogical approach which perceives the teacher as the deliverer of information while the student plays the passive role of receiver of knowledge acutely impedes the development of critical thinking skills (Marzano, 2007). Educational technology that requires students to create study groups about the subject content they are studying or by having them analyze the information available in existing resources is stressed as instrumental in stimulating critical thinking. Teachers need to integrate the content of different subjects and plan lessons that arouse curiosity and higher levels of thinking among learners during the teaching and learning processes.

Use of Assessment to Stimulate Critical Thinking

Educationists argue that use of effective assessment techniques stimulates critical thinking. Dessie and Heeralal (2016) aver that integrating assessment in instruction greatly influences the degree of absorption and internalization of content delivered in the classroom. They further report that most teachers are less likely to use different assessment strategies as part of instruction to assess high order thinking and collect evidence to identify learning gaps for future learning. Such activities have negative implications on the quality of education and by extension internalization of content. In this regard, school administrators, teachers and researchers should do more in the area to effectively implement formative and summative assessments to improve students thinking skills. Libman (2010) asserts that assessment and teaching should be compatible and aligned to support one another especially in the process of building the learners high order thinking skills which has immense implications on critical thinking.

O’Leary and Hargreaves (1997) aver that when assessment is carefully designed and accorded considerable thought, it encourages and motivates learners to develop appropriate generic skills. The upshot is the acquisitions of such generic skills as problem solving, thinking critically and making judgements in addition to knowledge and understanding. Teachers should realise that assessment is an integral part of instruction and a powerful means to improve internalization of desired educational outcomes. This involves acquisition of knowledge and critical thinking (Cowie, 2012). Moreover, teachers need to provoke students’ prior knowledge or schema through effective dialogue, questioning, self-assessment, open ended assignments, thinking and concept-mapping to support them to apply concepts, strategies in real situations (Hodgson & Pyle, 2010). Njoka (2012) argued that teaching and learning process should focus on developing high order thinking skills among learners to enable them effectively participate in the development of self and society. The use of assessment during instruction to promote critical thinking is based on the understanding that assessment could be used more than simply to test knowledge, but provoke learners to engage in higher order levels of reasoning and problem solving. In order to inculcate students with critical thinking skills, teachers should adopt such instructional techniques as use of self-directed learning activities, which involve project work, research, collaborative learning, group work, synthesis and analysis of collected data, critical evaluation of the subject matter, world views and discourses.

Integration of critical thinking is very important in teaching at the secondary school level because it promotes content analysis and evaluation which in turn have a positive impact on achievement of the students. In the area of critical thinking skills, few studies are available related to instructional design in Kenya. If teachers really want to modify the behavior of learners in the classroom, it is indispensable to facilitate the critical thinking component of education. Owing to the paucity of studies in the area of critical thing in Kenya, the researchers felt the need to investigate the level of critical thinking skills among learners from public secondary schools from Nyeri and Nairobi Counties in Kenya.

Results and Discussions

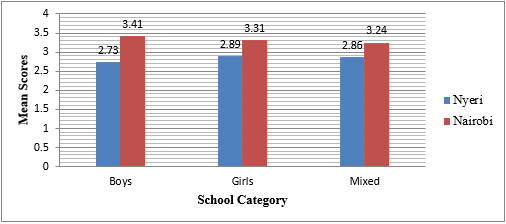

The purpose of the study was to assess the level of critical thinking skills among learners from public secondary schools in Kenya. Respondents were provided with items on a five point likert scale which required them to indicate their opinion regarding specific abilities that measured their critical thinking skills. The scores obtained were used to calculate a mean score (?̅) of critical thinking skills of the respondents measured on a scale of 1 to 5. The results are presented in Figure 1.

Figure 1: Critical Thinking Skills by School Category and County

Data analysis presented in Figure 1 clearly shows that learners in Nairobi County had higher levels of critical thinking skills compared to their counterparts in Nyeri County. In Nairobi County boys schools had a mean score of 3.41, mixed schools (3.24) and girls schools (3.31). In Nyeri County, students in girls’ schools had the highest mean score (2.89), mixed schools (2.86) while boys schools had a mean of 2.73.

The findings of the study concur with a study conducted by Aliakbari and Sadeghdaghighi (n.d) among Iranian students which established that students had low levels of critical thinking. The study further revealed differences between male and female students in critical thinking abilities, with male learners outperforming their female counterparts. Floyd (2011) states that there are widespread perceptions that students from rural areas have low critical thinking skills compared to learners from urban settings due to their strong cultural orientation. However, instead of this view, more credence is being given to aspects such as linguistic aptitude and educational experience as contributing factors to learners’ capability to exhibit high levels of critical thinking. The apparent deficiency in critical thinking abilities among students in Nyeri may be due to the fact that they had been raised under coherent societal norms where community welfare and traditional values are stressed beyond personal convictions. Consequently, rural communities place a lot of prominence on displaying regard for authority and conforming to the demands of societal values rather than standing out on individual convictions. This could be among the variables contributing to differences in critical thinking abilities between learners in Nyeri and Nairobi counties.

- It had been hypothesized that there was no statistically significant difference in critical thinking skills among learners in boys, girls and co-educational schools. To test this hypothesis, one way Analysis of Variance (ANOVA) was computed. The statistical relationship between the levels of critical thinking skills among learners in boys, girls and mixed public secondary schools was presented as shown on Table 2.

Table 2. ANOVA results on critical thinking skills among learners

|

|

Sum of Squares |

df |

Mean Square |

F |

Sig. |

|

Between Groups |

15.221 |

29 |

.525 |

.849 |

.694 |

|

Within Groups |

234.935 |

380 |

.618 |

|

|

|

Total |

250.156 |

409 |

|

|

|

Table 2 shows that the analysis of variance results yielded p-value = .694 which was more than the alpha value α > 0.05. This means that the observed differences in critical thinking were not statistically significant. Therefore the null hypothesis was accepted. The conclusion was that critical thinking skills of learners from boys, girls and mixed secondary schools were essentially the same.

These findings suggested that the overall critical thinking skills of learners in different school categories were the same. Peron (2010) observed no differences in critical thinking skills among learners in different school categories. This was attributed to similar classroom practices and instructional strategies that did not drive students to give evidence and to reason. Schools did not employ pedagogical approaches such as debates, brainstorming, essay writing and questioning techniques in a way that stimulates development of critical thinking in the classroom. As a result majority of learners did not develop high levels of critical thinking despite being in different school categories. Consequently, the similarities in the instructional methods in different school categories could be a contributing variable to similarities in learners’ critical thinking abilities.

- It had also been hypothesized that there is no statistically significant difference in critical thinking among learners from secondary schools in Nyeri and Nairobi Counties. To test this hypothesis, independent sample t- test was computed for the means of the critical thinking skills for learners from rural and urban environments. The findings are provided in table 3.

Table 3. Independent sample t- test

Data analysis presented in table 3 shows that the level of significance of .000 was less that the p-value (.05). Therefore the null hypothesis was rejected. It was concluded that the level of critical thinking skills among adolescents in Nyeri and Nairobi Counties were different. This concurs with Leipert et al. (2012) who observed that several features of the rural context, such as geographical, socio-cultural, economic, and health care contexts, are relevant to understanding the critical thinking skills of rural adolescents. Rural communities tend to be more religious and hold traditional values and beliefs, which can preclude rural adolescents from being assertive (Riddell et al., 2009). Therefore the contextual variables in the rural and urban settings could be stimulating acquisition of the critical thinking skills among the learners differently.

Conclusion

Descriptive data analysis established that learners in Nairobi County generally had higher levels of critical thinking skills compared to their counterparts from Nyeri County. The apparent deficiency in critical thinking abilities among students in Nyeri may be due to the fact that learners in Nyeri County have been raised under coherent societal norms where community welfare and traditional values are stressed. Rural communities place a lot of prominence on displaying regard for authority and conforming to the demands of societal values rather than standing out on individual convictions.

Inferential statistics results obtained from the computed value of ANOVA for the different school categories indicated the contrary. The differences observed were not statistically significant, suggesting that the overall critical thinking skills of learners in different school categories were the same. This was attributed to similar teaching methods across schools which could be contributing to similarities in learners’ critical thinking abilities. However, independent sample t-test indicated that there was a statistically significant difference in critical thinking among learners in Nyeri and Nairobi Counties. These differences were attributed to contextual variables in the rural and urban settings which could be stimulating acquisition of critical thinking skills among the learners differently.

Recommendations

The results of the study elicit several suggestions for the adoption of instructional methods in secondary schools in Kenya necessary in addressing the apparent deficiencies in critical thinking skills among learners. From the findings of this study, it is recommended that there is need to address the instructional procedures used by secondary school teachers in order to stimulate critical thinking skills among learners in both counties. It is important to note that schools in the rural environments are not inspiring learners enough towards acquisition of critical thinking skills. In this regard, secondary schools in rural areas ought to put in place mechanisms that compensate for this shortfall.

References

Aseey, A., Ayot, R. M., Oluoch, D.O. (2011). Principles of teaching and communication. a handbook for teachers and other instructors. Nairobi, The Jomo Kenyatta Foundation

Choy, S., & Cheah, P. (2009). Teacher perceptions of critical thinking among students and its influence on higher education. International Journal of Teaching and Learning in Higher Education, 20(2), 198-206.

Coon, D., Mitterer, J. O., Brown, P., Malik, R & Mckenzie, S. (2014). Psychology: A journey (4th edition). Toronto: Nelson Education.

Cowie, B. (2012). Focusing on the classroom: Assessment for learning. In Fraser, B. J., Tobin, K. G. & McRobbie, C. J. (Eds.), Second International handbook of Science Education (pp 679-690). London: Springer.

Dessie, A. A., & Heeralal, P. J. H. (2016). Integrating assessment with instruction: science teachers’ practice at East Gojjam Preparatory Schools. Amhara regional state, Ethiopia. International Journal for Innovation Education & Research, vol. 4, No. 10, 53-69.

Dindigal, A., Aminabhavi, V. (2007). Psychosocial competence scale. Ph.D. Thesis, Unpublished. Dharwad: Karnatak University Dharwad.

Floyd, C. (2011) Critical thinking in a second language. Higher Education Research & Development, 30(3), 289-302

Gilky, R. and Howard, H. (1977. Definition and glossary of terms. Association for education and technology. Washington DC.

Hayes, K., & Devitt, A. (2008). Classroom discussions with student-led feedback: a useful activity to enhance development of critical thinking skills. Journal of Food Science Education, 7(4), 65-68.

Healy, J. (1990). Endangered minds why our children don’t think. New York: Simon & Schuster.

Henderson-Hurley, M., & Hurley, D. (2013). Enhancing critical thinking skills among authoritarian students. International Journal of Teaching and Learning in Higher Education, 25(2), 248-261.

Hodgson, C. and Pyle, K. (2010) A Literature Review of Assessment for Learning in Science. Slough: NFER.

Jenkins, R. (2009). Our students need more practice in actual thinking. The Chronicle of Higher Education, 55(29) B18.

Jensen, E. (2005). Teaching with the brain in mind (2nd Ed.). Alexandria, VA: Association of Supervision and Curriculum Development.

Knodt, J. (2009). Cultivating curious minds: teaching for innovation through open-inquiry learning. Teacher Librarian, 37, 15-22.

Kokkidou, M. (2013). Critical thinking and school music education: Literature review, research findings, and perspectives. Journal for Learning through the Arts, 9(1),

Kothari, C. R. (2004). Research methodology methods & techniques. New Delhi: New Age International publisher.

Law, C., & Kaufhold, J. A., (2009). An analysis of the use of critical thinking skills in reading and language arts instruction. Reading Improvement, 46, 29-34.

Libman, Z. (2010). Alternative assessment in higher education: An experience in descriptive statistics. Studies in Educational Evaluation, v36 n1-2 p62-68 Mar-Jun 2010

Marzano, R. J. (2007). The art and science of teaching. Alexandria: Association of Supervision and Curriculum Development.

Matheny, G. (2009). The knowledge vs. skills debate: A false dichotomy? Leadership, 39-40.

Maundu,J.N., Sambili, H.J., Muthwii, S.M. (2005). Biology education: A methodological approach (New Revised Edition). Nairobi: Robkim Publishers.

McCollister, K. & Sayler, M. (2010). Lift the ceiling: Increase rigor with critical thinking skills. Gifted Child Today, 33(1), 41-47.

Mendelman, L. (2007). Critical thinking and reading. Journal of Adolescent and Adult Literacy, 51(4), 300-304.

MoEST. (2013). Secondary life skills education teacher’s handbook. KIE, Nairobi.

Nyeri County education Office. (2013). Annual Report. Unpublished.

Mutuma, L. (2011). ICT in Education: An integrated approach. Nairobi: Rinny Educational and Technical Publishers.

Mukwa, C.W.( 2015). Integration of educational technology in teacher education: A vantage for teacher training at county level in Kenya. Moi University inaugural lecture 22 series no. 1, 2015. Eldoret: Moi University press.

Mukwa C.W and Too (2006) Educational communication and technology (Part one) General Methods. (ECT 200) Nairobi University Press.

Mukwa, C.W. and Too, J.A.(2001). General instructional methods.. Eldoret: Moi University press.

Njoka, J. N. (2012). Measurement and evaluation in education in Kenya: An analysis of the 8-4-4 KCSE examinations. Berlin: Lambert Academic Publishing.

Nyonje, R. & Kagwiria, E. (2012). ‘Implementing life skills programme in Kenya: A learning experience for educational planners and managers.’ Kenya Journal of Educational Planning, Economics & Management, vol.5, no. 5, December 2012.

O’Leary, J. & Hargreaves, M. (1997). The role of assessment in learning. In Hargreaves, M. (Ed), The Role of Assessment in Learning. ASDU Issues, Queensland University of Technology, Brisbane.

Otunga, R.N., Odero, I.J. and Barasa, P.L. ( 2011). A handbook for curriculum and instruction. Eldoret; Moi University Press.

Peron, S. J. (2010). Teaching methods and critical thinking: a case of high school students in Kwa Zulu Natal. International Journal of Adolescence, 51(4), 300-304.

Rowles, J., Morgan, C., Burns, S., & Merchant, C. (2013). Faculty perceptions of critical thinking at a health sciences university. Journal of the Scholarship of Teaching and Learning, 13(4), 21-35.

Rowles, J., Morgan, C., Burns, S., & Merchant, C. (2013). Faculty perceptions of critical thinking at a health sciences university. Journal of the Scholarship of Teaching and Learning, 13(4), 21-35. doi: 10.1177/2048872612472063

Sadker, M. & Sadker, D.. (2003). Teachers, schools, and society. 6th Ed. New York: McGraw-Hill.

Simiyu A. M. (2000). The Systems Approach to Teaching. A Teacher’s Handbook. Eldoret: Moi University Press.

Smith, V. G. & Szymanski, A. (2013). Critical thinking: More than test scores. International Journal of Educational Leadership Preparation, 8 (2), 15-24.

Snodgrass, S. (2011). Wiki activities in blended learning for health professional students: Enhancing critical thinking and clinical reasoning skills. Australasian Journal of Educational Technology, 27(4), 563-580.

Tsai, P., Chen, S., Chang, H., & Chang, W. (2013). Effects of prompting critical reading of science news on seventh graders’ cognitive achievement. International Journal of Environmental & Science, 8(1), 85-107.

Tsui, L. (2002). Fostering critical thinking through effective pedagogy: Evidence from four institutional case studies. Journal of Higher Education, 73, 740-763.

VanTassel-Baska, J., Bracken, B., Feng, A., & Brown, E. (2009). A longitudinal study of enhancing critical thinking and reading comprehension in title i classrooms. Journal for the Education of the Gifted, 33(1), 7-37.

Willingham, D. T. (2009). Why don’t students like school? A cognitive scientist answers questions about how the mind works and what it means for the classroom. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass